The Remand Home

Apart from the newspaper reports, the material below all comes from Peter Thorogood, the son of the superintendent at the Home. Many thanks to Peter.

Above: Information from booklet on the Remand Home, 1940s

Western Morning News 31 July 1943 p4 col3

The following year a handyman was required, for general duties and to give some woodwork instruction to the boys.

Western Morning News 6 October 1944 p1 col5

There was also a vacancy for the post of Deputy Superintendent at Ashburton Remand Home. The salary would be Burnham scale II for a certificated or non-certificated teacher, plus a war bonus of 9s 6d per week. Full board, lodgings and laundry would be provided.

Western Morning News 2 October 1944 p4 col4

1945 After a boy at the home received bruises, Mr J Cock suspended the deputy superintendent of the remand home from duty. The sub-committee of the Devon Education Committee resolved that the deputy's employment would be terminated.

Western Morning News 27 April 1945 p2 col3

In 1946 a 16 year old boy at Plymouth Juvenile Court heard that he was to be returned to Ashburton Remand Home. Although earlier he had said that it was 'pretty good', he now burst into tears and threatened to kill himself if he had to go back. He was carried out of the courthouse.

Western Morning News 4 December 1946 p6 col6

When the post of Assistant Matron was advertised in 1947, the school accommodated 35 boys. The initial salary was £200 per annum.

Western Morning News 24 March 1947 p4 col2

1947 A 9 year old boy who had absconded twice from the Home was further remanded for a week for a psychiatric report. Amongst other charges he had, with an 8 year old, broken into a house in Devonport and stolen a milk jug and sugar bowl.

Western Morning News 12 November 1947 p3 col2

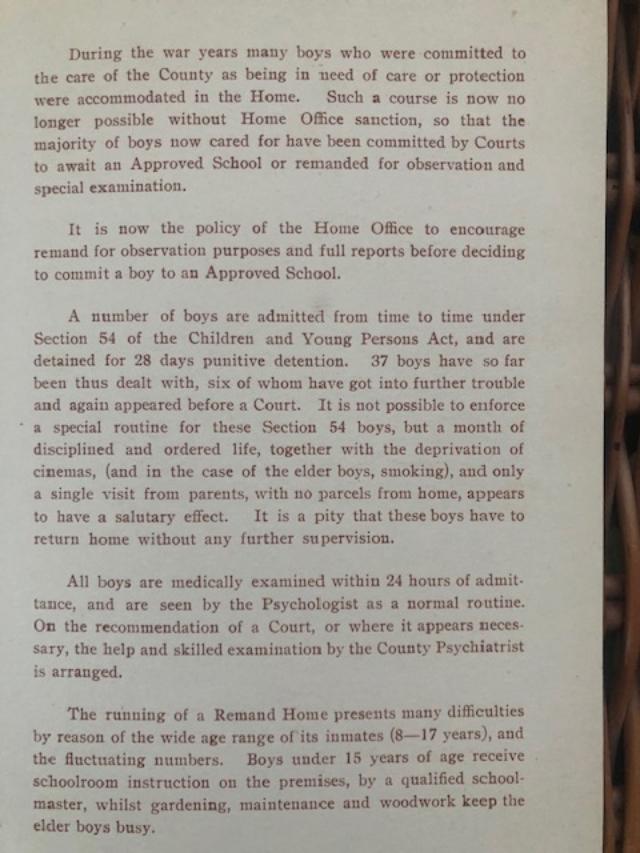

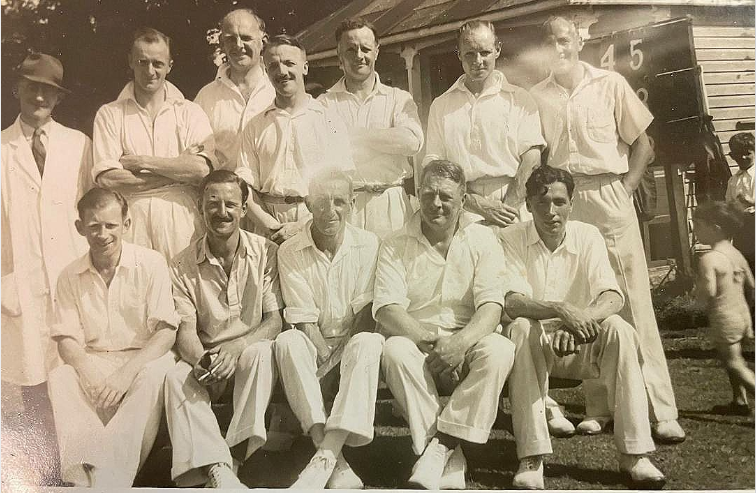

Above: Open Day 1949.

North Devon Journal 12 January 1950 p4 col5

1953 A document in the National Archives is concerned with the future use of the Ashburton Remand Home, Balland Lane; a further document from the 1950s details the high cost of maintenance and closure.

National Archives http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk ref BN 62/3248 and BN 62/1549

By 1958 the remand home had closed - the Ashburton and Buckfastleigh County Secondary School opened in the premises in 1958. (At least I think it did. I have seen someone claim that they went there in 1957)

***

Growing up at the Remand Home

Peter Thorogood's father, G F Thorogood, was Superintendent at the remand home during the 1940s and 50s. Here are Peter's reminiscences: many thanks for both the text and the images

When I was asked by an army officer, "Thorogood, how far away is that cow?" I answered, "400 yds sir."

"Very good; how did you decide that distance?"

"I estimated it, halved it, and doubled it, sir."

"Very good Thorogood; how would you capture that cow?"

"I wouldn't sir, I like cows."

"WRONG ANSWER, FAIL."

I decided that was enough of the cadet force. I left, but that is 11 years later.

The House and Laburnham tree

I don't remember the Open Day in 1949, so I will start from my first memories.

Jill had an unusual life. She had a long beard and a long chain, and her breakfast was stolen from the breakfast tables, where my friends were eating, before going through the kitchen, past the scullery, past the small pantry, through to the bread-room.

Loaves of stale bread vanished in minutes.

Above: Peter with inmates

She spent the rest of the day butting the wire fence where Lindy our terrier barked from the other side. Lindy was my second dog. The first dog was called Chum: he was a Keyshound, and he was big, like a friendly wolf. He was my best friend, and would let me sit on him, then turn his head and lick me.

Jill slept alone in her stable, which was next to the garage where the Rover lived, and a dozen rabbits who chewed and slept all day. Jill sometimes slept peacefully with a male teenager.

I had an ever-changing group of friends who arrived in police cars. I had many rides in police cars, usually round the back yard. I wore 100s of police helmets, and I would like to go to the kitchen to watch the two policemen who bought me new friends drinking tea and biscuits. I would creep into the white Ford Zodiac, sit behind the wheel making ringgg ringgg noises.

Lunch was at 12:30 exactly, when the gong would sound, and my friends would appear in a long line wearing knaki shorts and grey shirts. We would sit in tables of five. Sometimes one of my friends would already have a plate of dry bread in front of him, and he would be wearing white shorts and a vest. The rest of us had meat and two veg.

Outside there were white pigeons, but they might have been doves, living above the kitchen in their own house above the kitchen yard which was very steep and difficult to skate on. It was always covered with white pigeon poo, which sometimes Mr Luckson would scrub away.

The coal man, Mr Smerdon, would grumble; he said words that I didn't know, as the dirty black bags became awkward, walking down the steep slope before he lent forward pouring bag after bag down into the chute to the cellars, past his black capped face. Mr Smerdon never said anything, just dropped his coal and folded his bags. I didin't like him, and his horse wanted to bite me.

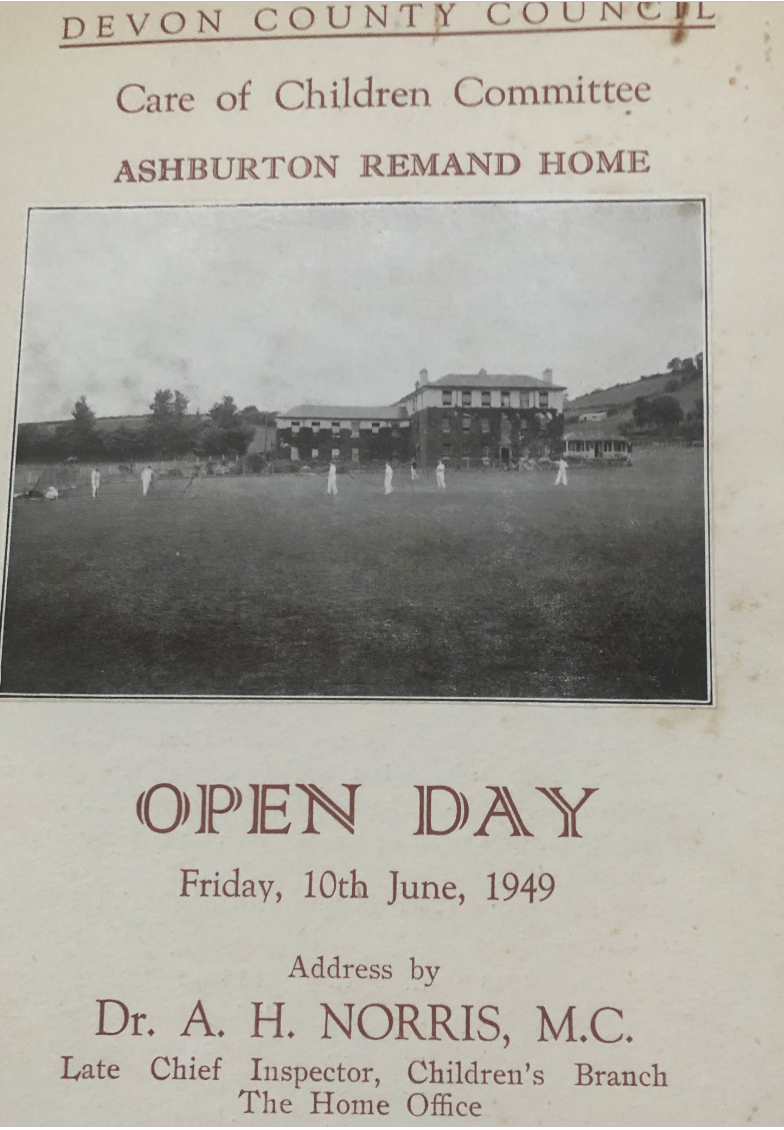

Left: Peter Thorogood, early 1950s

With many thanks to Peter

Mr Luckson, the gardener, lived in one of the council houses at the top of the back vegetable garden. He was from a place called Cornwall which was a long way from Ashburton. He had a new television, and sometimes we would go up there on a Sunday. My dad and Mr Luckson would have a small glass of sherry and laugh about the vicars on the television. There were lots of vicars with crosses, and they were dressed in white clothes. One vicar kept swinging a gold thing that was on fire. They kept bowing to each other and never walked much. It was a bit like a silly tag, but they didn't touch and say 'it' and run away. I told my dad I didn't want to be a vicar on the television, which he thought was very funny. Mr Luckson told me I would have to go to church every day to get on television. My Dad would ask Luckson the gardener, had the vicars ever learnt semaphore, as their hand signals were no good. My dad called them bishops, which is part of a game called chess. He would reply, 'I wonder if they have lost something, George, spending all that time grovelling on their knees.' This was obviously very funny. My mum, who was called Olive, but was always called Bobby, would interrupt, telling them to stop being silly.

Above: Mr Luckson with P Thorogood on left, and group of inmates

The bread van came every day, a little grey van full of long square white loaves. Sometimes we would have 30 loaves. On Wednesdays, the baker would bring cakes. I used to hide in the row of fir trees in front of the great big static water tank, which was covered with green slime and wire netting, where my tadpoles lived. It was worth the wait to run out and steal some cakes while the baker was at the back of the house loading square loaves into the bread-room: down the steep slope past the barking dog and angry goat, under the pigeons.

Mr Lang the butcher had a big shop in Ashburton. I heard my Mum ordering six dozen sausages, four legs of lamb, three ribs of beef, pounds of lard and twelve dozen eggs. There are twelve eggs in a dozen unless it's a baker's dozen when there are more, which is silly. I told my Mum to get eggs from farmer Sam; she said he didn't have chickens. So, when I went to milk the cows, I told him to buy chickens. Mr Lang would come in a white van and it seemed that he would empty all his van into our larder.

After breakfast we would all play cricket in the big back yard. The men and my Dad, who was called George, but no one ever did, would bowl downhill at me and my friends with a tennis ball. They called him "Sir" or "Thoro", which is part of my name. You were out if the ball hit the white stumps painted onto the grey wall. If the ball went into the vegetable patch you were out, and if it went over the garage, or into the flower garden. Throwing the bat down was not allowed; if you did you had to run in circles with the boys in white. If the ball went over the garage it was fun, because we would all look in the bushes, never finding the ball, but my Dad and the men always stood in the yard carefully watching us.

After breakfast my friends went to class in the big long room, and I hated them being in class. The big silver horn record player with the wind-up handle was at the end, next to the fire escape door. I loved to sharpen the old needles, in a little box with a grinder inside. It wasn't fair that I couldn't try my new needles on the spinning black record. I tried to count how fast it was spinning - they said 78 times, which is nearly 100. The Rover could do 100 easily, my Dad said. I only counted the record going at 10 because the box of needles, which were easy to count, would fly off. When I put a new sharp needle on a 78 times record my Dad or one of the men would tell me off. There was a piano next to the big revolving 78 player, and a brown Bakelite radio, a sort of plastic, on a shelf just out of my reach. I would like to play with one finger: Baa baa black sheep was easy. I used to climb up to the radio at a quarter to two every day and find the Light programme and hear, "Listen with Mother". Sometimes in the evenings I would go and listen to "Journey into Space" with Jet, Doc and Lemmy. It was dark at the end of the big hall and I often had to run and hide from the spacemen. Sometimes I would try and play the piano in the morning after cricket while school was starting, and the men would tell me off.

So I was not happy when they were being taught. I would sit in the laburnham tree outside the side front door, waiting for a white police Ford Zodiac to bring new friends. I would climb to the top and look down and see the lighthouse in the window at the end of the corridor, above the side front door next to my bedroom. I noticed that important people came to the side front door which was always in the sun, just under my tree. The policemen and other people were always sent to the back yard door where there were basins and rows of toilets.

Above: Laburnham tree and smart entrance

Mr Luckson would always be found in the vegetable garden which was off to the left of the big back yard, and to the left of the garages and the big field. He used to grow beans, lettuce for the rabbits, onions, cabbage, rhubarb and huge tobacco plants. He would show me butterflies and caterpillars. Sometimes he would be sitting in the sun on a stool, smoking his pipe, in front of the potting shed, which was full of drying tobacco leaves hanging from the roof. He was short but was always suntanned. Sometimes he would wheel a barrow into the kitchen yard full of vegetables. He told me Miss Bunclark, the cook, didn't like him bringing up the vegetables in the morning as she had to put them in the larder, and she was always too busy cooking. I grew up to learn that Miss Bunclark went home after lunch, which we called dinner.

Miss Bunclark lived in a very ugly three storey house at a place called Traveller's Rest, near Bickington. She wore a hair net with pins. She came on the bus, but often she didn't arrive, so my Dad used to fetch her in the Rover. She didn't like me being in the kitchen, which was always full of steam, and she would send me out. She wasn't fun and never laughed.

At the back of the kitchen yard to the left of the fence where Jill and Lindy got bored, was the cricket pavilion. This was also the woodwork room because it had a lathe in it and planks of wood. One of the men - my Dad told me they were called staff - was called Mr F. I didn't like him: he wore a silly beret, had rosy cheeks, a long nose, a brown coat, a ruler in his pocket and a pencil behind his ear. He never seemed to do any woodwork, and never liked me playing in the pavilion, where he would teach my friends how to use a hammer and a screwdriver and a plane. None of my friends liked him either. I made a catapult with some strong rubber that my Dad bought me from Church's Ironmongers in Ashburton. I used to hide in the fir trees and wait for Mr F and shoot him in the back with stones. I didn't hit him many times, but one day he caught me and pulled me by my ear into the kitchen and to my Dad's office.

I do not remember the other men or staff or their names, but I started to hate my Dad when he would put on his grey coat like Mr Church the ironmonger's, and take a rabbit from its hutch, hold it by the ears and back legs and pull it apart until it was dead. He would do this to 3 or 4 rabbits. He would pin them by their ears on the garage door where the Rover lived, cut off their skin, cut them down the middle and put their steaming innards into a bucket. They would then go into the kitchen.

Our sitting room was green and cold; it was in the real front of the house which they said faced south. It was at the top of the drive on the right above the tennis court and the geranium terrace. There was a circle of grass for cars to turn in front of my laburnham tree, with a flagpole, and the real front of the house was around the corner.

We had tea in the sitting room which was cold, so my Dad would go into the cellar, where there were big fires in boilers, bigger than the steam train at the station, which was called "Bulliver". He would return with a huge shovel of glowing coals, which he would throw into the fireplace - instant coal fire. Mum would now say, "Look at the mess on the carpet".

"Only footprints", my Dad would reply.

I can't remember what we did in our sitting room; I didn't like it so I would go to the corridor window next to my bedroom, and put a wire on the battery that lit up the torch bulb on the lighthouse. Then I'd go downstairs, climb the laburnham in the dark, and watch it shining.

My bedroom was at the end of the corridor on the corner of the house; my sister Wendy had a room next to me which was much bigger. There was a door opposite her bedroom with a Yale lock that opened into my friends' parts of the house. Then there was the bathroom and my parents' bedroom, which was big, and next to that was the airing cupboard, which was always hot and had lots of balls of wool to play cats' cradles with.

My friends would sleep in dormitories through the Yale door: the big, long one above the dining room where there were 18 beds, a smaller one somewhere on the top floor and another big one in the front of the house above my bedroom. There was a staircase leading up to the dormitories where the door with the Yale lock was. The fourth and ninth stair had a special switch which would sound a bell if you stood on them.

There was also a sick bay which was always locked. I found that I could easily get in there with my mother's bunch of keys that she left out. She was called Matron and was the important lady who looked after the kitchen, the cleaning, laundry and ordering food. She wore a white coat where she should have kept her keys.

My Dad said we had 35 beds, but that was too many: I could not understand why we had too many beds. I loved to explore the top of the house, where no-one ever went in daytime. I could look a long way down to the big back yard, the garage, stable and rabbit hutches, and the north drive which was a bit overgrown. I could see my sandpit and swing at the right end of the yard near where the horses would stop in front of the clothes line, and the big back vegetable patch. If I went to the front of the house I could see down the drive and out over the tennis court, and the big field where Jill would sometimes go when she broke her chain. Then she would get through the fence and into Balland Lane, where we always found her chewing a bush.

Sometimes my Dad would not bring Jill in to eat from my friends' breakfast plates. He would be roaming downstairs looking very unhappy and spending a lot of time on the phone. My Mum would tell me that some of my friends had run away, or as she said, absconded, which was the way to tell important people that they were not in the building. My Dad would drive off in the Rover with one of the staff, and there would be no morning cricket; the back door and kitchen doors would be locked. The Rover would return and sometimes a police car. There would be a lot of shouting and doors banging; I would hear people going up stairs shouting, more doors banging, then silence. I remember then hearing the noise of a cane and screams. My mother told me they had been naughty running away. They were the friends who were in white shorts and had to run circles around the big yard. I realised that this was to frighten others from running away, and I didn't like my Dad again.

Mr Luckson had a friend who was a farmer, just at the top of the north drive, which had been cleared. I would climb the gate, which was more fun than opening it, and cross the lane and go into the milking shed. The farmer, whom I only knew as Farmer Sam, let me help him milk a cow, but I wasn't any good. He would tell me, "You do it like this", and squirt warm milk at me.

Farmer Sam put his sheep into our big field every year, but they had to go before the cricket season started. One of the sheep was a ram and would try to steal Jill's food. The ram and Jill would fight until one of the men separated them. One year when I was flying my kite I saw them fighting, and then the ram was lying on the ground and Jill had only one horn left. Someone called a vet, who injected the ram and put something hot on Jill's broken horn. The ram went home with Farmer Sam.

Miss Bunclark was hardly ever coming to cook, and I was told that my Mum could not do all the cooking, and that Mrs Muggeridge [Mugridge?] from Ashburton was going to be cook. I hid in the kitchen waiting to see if I would like her. She was very tall, didn't have a hairnet, and laughed a lot. She also smelled of cigarettes. When I got to know her she would cook me special breakfasts: beans, scrambled egg, bacon and anything in the larder. At teatime she would make me huge roast beef sandwiches from big lumps of cold roast beef in the larder.

She was such a good cook that my Dad promised her a refrigerator. Three people struggled to get it down the kitchen yard and into the storeroom where the potato peeler lived. It was bigger than the wardrobe in my bedroom. It had a big electric motor and a big belt, that I was told would cut my finger off. It was very loud and never seemed to stop. It often went wrong, and someone in a plumber's suit would be lying on the floor fiddling inside. My favourite job was to fill up the potato peeler: I had to stand on a chair to look inside. I would fill it with potatoes, turn on the water and turn the switch. After some time, we would put a big saucepan on the floor under the door and open it, and white potatoes would tumble out. One always stayed inside. I wasn't allowed to take it out, but I did. There was a big pot in the storeroom, which was the top of the milk churn ladled out, warmed in the kitchen and then stirred and cooled in the storeroom. Our own clotted cream.

Sometimes I would go into Ashburton with my Dad. He would have to get medicines for my friends, and things from Church's the ironmonger. The ceiling in the shop was extremely low, and my Dad would always hit his head on the beams. Mr Church always wore a dark grey coat. The shop had a wonderful smell of new parts and shiny hinges, nails, brushes and buckets. I think we went there nearly every day. My Dad would sometimes go into the sweet shop and buy me a wagon wheel. One day I was left in the Rover while my Dad went to pay the newspaper shop for the Western Morning News, the Daily Telegraph and the Radio Times. I was sitting in the driver's seat, but the hand brake was pulled hard locked. There was a button that I kept pressing: it made a noise like the car starting up. Then the noise stopped, and smoke came from the engine. My Dad came running out of the newspaper shop and jumped into the car. He tried to start it, but nothing worked - he was very cross. He had to start the Rover with a handle. He drove me home telling me to keep my finger away from the buttons. He said I had set fire to the starter motor which cost a great deal of money.

The time was coming when I would be starting school. I had been spying on M F., creeping round the back of the workshop. I was right, he was lazy - he was caught eating sandwiches and drinking from his thermos flask. Later on there was sawdust everywhere, as Mr F had left and Mr Eliot had joined the staff in his place. He was very good at woodwork, and made lots of chair legs on the lathe and let me help him.

Above: The sandpit and cricket pavilion/workshop. The author is on the extreme left.

He was good at cricket, running and anything. He used to be head of the shoe shop called Frisby's in Ashburton, where my sandals came from.

I was getting good at cricket: the painted stumps had been replaced by bits of broomsticks pushed into a block of wood. We didn't look for balls hit over the garage because this was when my friends would run away. It was 6 runs and out. Cricket was played after breakfast, dinner and tea.

Behind the garage and the stable and the rabbit hutches there was a field with a big hill. At the top there was an old quarry overgrown with grass. I wasn't allowed to go into the field, but I did when no-one was watching. Sometimes my Mum would take me into the field to pick primroses and wildflowers. She always walked up the hill and I saw that all grown-ups walked up hills. I would run to the top and do long roly polys down into the quarry. My Mum told me not to, because I might bang my head, but I didn't mind. I had banged my head before and my brains didn't fall out. That was my favourite place. Sometimes my Mum would make me a little picnic and pack it in my satchel. I would take Lindy with me and sit on top of the quarry and eat it. One day Lindy wasn't well, and my Dad put her in the Rover and drove away. She didn't come back. I didn't like the name Lindy: I thought it sounded soppy. My Dad said we were getting a new dog: he was called a labrador and I called him Simon which was a nice name.

On Sundays we would all dress up, and my Mum and Dad and all my friends would go to church in Ashburton. We had special seats next to the organ. My father and sometimes one of the staff would sit behind us. I would watch Mr Peachey the postmaster playing the organ. He always played boring slow music as we walked in, often repeating the same notes while he looked for the vicar Mr Jones to appear in his crumpled white cloak. I was told that the vicar was not called Mr but Reverend Jones, so I called him Mr Jones the Vicar. Reverend was difficult to say and sounded important, like calling my Dad Superintendent, which no-one understands. Then we would sing a hymn. Mr Peachey wasn't very good, and sometimes the organ went so slowly he was left behind. When we walked out we were always last. Mr Peachey tried to play some loud music but I knew he made mistakes. I had to shake hands with the vicar Mr Jones outside. He would pat me on the head.

There were lots of people at church every week, and they would all be very smart: some ladies had ugly hats and some men had hats but did not wear them. After the service which was long and boring my Dad and Mum would take ages talking and would even walk home talking. Dr Mills seemed to be a friend of my Dad and Mrs Mills would talk to my Mum. David and Robin, who were Dr Mills' sons, didn't talk to me.

Sometimes in church, which was always cold, the electricity would be switched off - they said it was a power cut. Mr Andrews, who was a friend of my Dad, was called Reg; he would bring candles around. Mr Peachey the postman would get off the organ seat and whisper to my Dad. He would get one of my friends to go with him through the curtain behind the organ. That was to put air in the organ with a big handle which went up and down. My Dad promised that I could pump when the next power cut happened. My Mum told me to pay attention to something called a sermon, but it went on and on, about the scriptures and the word of the Lord and was not an adventure story. My friends would talk sometimes, and my Dad would tap them on the shoulder and looked terribly angry. Mr Peachey sometimes played wrong notes that sounded horrible.

When I was a bit older I was first behind the curtain when there was a power cut. It was hard pumping up and down, but I didn't have to listen to the sermon, and would find bits of bamboo stick, and rubber rings like polo mints, that I was not able to eat, but they fitted over my fingers. I think they were organ bits. Mr Peachey the postman would put his head around the curtain and say, 'Pump now'. Then everyone would sing, and the organ was very loud. When it was loud I had to pump awfully hard, and got tired. Sometimes I slowed down, and the organ would sound funny and someone who I didn't like would come and pump instead. Then they went away. I was cross, so I thought, when the next hymn comes, I am going to stop in the middle. Mr Jones the Vicar said, 'We will sing a psalm'.

I pumped a bit but the organ was quiet, so it was easy. I tried to see how slowly I could pump. The slower I went the funnier the organ went, and then I would speed up. The psalm seemed to go on forever and I was very tired, so I stopped and went back to my seat. Nobody was singing. I watched my Dad shaking and my Mum as well. I looked around the church, and everyone was hiding their face in their hats, or laughing. Even Mr Peachey and Mr Jones were smiling. Mr Jones the Vicar said, 'Let us pray'.

Sunday lunch was always a big roast, and was cheerful with lemonade and orange juice and sometimes ice cream with clotted cream. After this the afternoon hike was next. My Dad and Mum would put on stout shoes and the whole house would walk in a long line of two. We sometimes walked six miles to Cold East Cross, or Buckland where God came with the Ten Commandments, which he wrote into some rock. God had very strong fingers. Sometimes there would be a very long walk to Haytor, which was too far for me.

Above: A Sunday walk to Haytor

My Dad made me a go cart from old pram wheels. It had two bits of wood to sit on and a bit of wood with the front wheels that I could turn with my legs. It had a brake, which wasn't very good. I was very good at pushing it up to the top of the big yard and driving down until it was too fast and turning it back up the hill to slow it down. One day I would be able to drive down the big yard, past the corner of the house, past the flagpole and round the grass, all the way to the bottom of the drive, which was a long way. I think it was 3 miles to the flower beds. But at the end of the drive there was a steep slope down into Balland Lane. I would not be able to stop. There was a sign my Dad had made there, it said, 'Drive Slow'. I heard important people who came into the side front door under my laburnum tree tell my Dad it was bad grammar.

My Mum and Dad took me to Newton Abbot to buy school clothes. I was going to the same school as my sister Wendy, who was 7 years bigger than me. Buying clothes was very boring but Clarks shoe shop had an x-ray machine with buttons on the side that showed the bones in my feet. I was only allowed a quick look but I went back when no one was watching. There was a place to look for grown-ups and a place where I could see in. There were a lot of little bones in my feet.

One day coming home in the Rover, I was playing in the back, and my Mum said I opened the door and fell out at 30, which is slow, not nearly 100. My Mum said I had cut my head open, but my brain had not fallen out. She was very cross with my Dad. They said I fell into mud, and I was lucky because there was usually something a farmer would leave there like a roller, but it was only mud. My sister Wendy told me I was lucky I wasn't dead. She made me cry a lot; I hated my sister. My mother made me very cross because she often wanted to look at my head to make sure my brains were not falling out, and I knew this was silly. I started to hate my mother as well.

I had a tent around my sandpit which was a castle inside: it was next to the big wooden swing that I could just get on, but I needed a push to start. So I would not play cricket but sit on the swing and ask one of my friends to push me. Sometimes my Dad let a friend stay and play with my toys in the sandpit, and catch tadpoles with me in the big static water tanks. Sometimes we would go out into the big field with a box kite which was made of aluminium which they said was very light. It was yellow, and when it was in the air I would let the string run from the ball, which cut my hands sometimes because it pulled very hard. My Dad would see it in the sky and join in. He would have more balls of string, and would tie another ball, and then another, and let the string out. Sometimes I could not see the kite, as it was extremely high: my Dad was very excited. We would put a strong stick in the ground to tie the string up and go into the house and get everyone to come and look.

I had to go to bed at 7 o'clock which was not fair: I hated both my Mum and Dad. They would play tennis outside and I could hear them shouting and laughing; sometimes I could see a high tennis ball through the curtains. I would get out of bed and watch and they would see me and shout at me to get to sleep.

Often a hedgehog would get caught in the tennis net. We would give it milk and untangle it. My Dad said they were full of fleas. Sometimes moles would make holes in the tennis court, and my Dad and one of the men would have two shovels and try and catch the mole. They were not very good at it. A man would come with a bag with a ferret in it and put it in a hole.

The tennis court had water pipes under it, and they would break, so one of my friends would dig a hole and a plumber would come with a blow torch and shiny silver which he would drop from the blow torch. He would never fill in the hole, but I didn't mind because it stopped anyone playing noisy tennis.

All my friends had to see a doctor when they arrived. There were two doctors in Ashburton: Dr. Bellamy was very nice, Dr. Mills was frightening. They would examine my new friends, some were not nice, and they were sometimes painted with purple paint on their face and arms and legs. I was used to purple faces, but some were nearly painted over their arms. My Mum used to tell Mrs Muggeridge to put the 'Impytigos' on their own table. Mum would not explain what an Impytigos was.

If I was ill I would stay in my parents' bed in the day time, and a doctor would visit me. My Dad called Dr. Bellamy Dick. He went salmon fishing, and swimming with no clothes. He put a glass thermometer under my tongue very gently and counted to sixty with me. Then he would look in my mouth and feel my tummy. He would sometimes leave a little box of cough sweets. Dr Mills, who was called Sandy because he had red hair, scared me. He would shoot pheasant and deer on Dartmoor. He would come in and stare at me, his face was always angry, and then he would say, 'What's wrong now?' He was not so gentle with the thermometer and didn't count with me but went off with my Dad to talk. Sometimes I had the thermometer in my mouth for an hour. I did not like Dr. Mills.

There was a big boy called P, who wasn't one of my friends, who had his own bedroom and was allowed to smoke cigarettes. I think his brain was different because he would sometimes sleep with Jill the goat in her stable. He caught the bus every day to a college called Seale Hayne, near where I fell out of the car, to learn to be a farmer. He didn't say much but when he spoke his head woulld twitch. I didn't like P, but I didn't hate him like lazy Mr F. No-one would explain why P was in the school. One of my friends said he was spying, so he slept with Jill so that we would forget him. I told him that was silly, because spies were dressed up in raincoats, and P didn't even smoke a pipe. So, he was not one.

Sometimes we would go out and come back late. When we went into the kitchen and turned on the light, big beetles would run into all the cracks and under the cupboards and the big cooking stoves. We would try and stamp on as many as possible, and chase them down the concrete corridor. My Dad would sweep them all up into a shovel and take them out to the dustbin. Every time we turned the light on we would do the same. Sometimes we would turn the light off and stay and then surprise them when we turned the light on again. There were hundreds of them. I was told that a special poison had been put down but they were very hard to stop as they kept having children. It was fun for a while but it became a bit of a nuisance, especially when I was a bit older.

I tried to find out how to measure my brain, but my Mum said it meant taking brain tests. I told my Mum I was stealing sawdust, but it tasted awful*. There were no brain tests in my I Spy books, and I used to ask my friends if there was any sawdust in my ears, but there was never any. Anyway, I had a new native American hat that came down to my trousers with bright red and green and yellow feathers. It was difficult to spy on anyone with my headdress on. I would hear people say, 'We are being spied on, don't look.'

[*Peter had heard his father talking about people with sawdust in their heads]

The best toy I ever had was a read Mahmood steam engine. My Dad put some spirit in a burner and some water in a copper tank that looked a bit like Bulliver in Ashburton station. Then we would light it, steam would start to come out, then there was a little shiny lever that let steam into a piston and a wheel would go round. I loved playing with it - none of my friends knew what a piston was, although they were into cars as well.

The water tanks behind the fir trees were full of frogs or toads. Frogs are greener than toads. But they didn't look happy and were trying to get out, and some of them died. I had a place where no-one would notice with some sticks that floated and I lifted the wire netting. Sometimes there would be four frogs on my boats so I had to make more boats and push them with a long stick, so they could climb out where the netting was lifted up. I had five or six boats, and nobody noticed. I sometimes saw frogs near the tanks: I think they were saying thank you for the boats.

I was starting school but my big sister Wendy watched everything, even when I ran down the lane in front of her shooting the enemy.

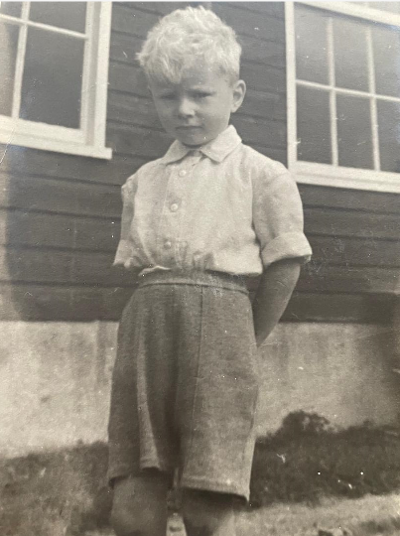

Left: Peter with Lindy

***

Peter's father kept a diary of his time as superintendent of the remand home.

Here are some extracts:

Above: G F Thorogood, back row, third from right

April 1943

My wife and I (Mr and Mrs G F Thorogood) and our daughter take up residence in the late Ashburton Grammar School Hostel, which is to be opened on 1st May as a Remand Home.

5 boys transferred from Pinhoe Remand Home arrive in evening. M, one of these lads, has scabies and is ordered by Dr Hall to Isolation Clinic.

May. M taken to Newton Abbot.

Mrs Boon arrives to act as a temporary cook.

Remainder of lads - 18 in number, arrive from Pinhoe.

No domestic help and acute shortage of cooking utensils.

Mr Widgery, a supply teacher from County staff arrives.

Sand pit made and filled with large load of quarry sand.

Mr Brooking (our gardener) does not wish to associate himself with our lads and tells them so.

C brought back by Exeter police.

Mr Brooking decides to resign. Told to carefully consider the matter.

Cinema show for lads in Town Hall.

Juniors commence school under Mr Widgery.

Mr Brooking leaves.

Mrs Fall (sp?) commences duties as cook.

Mrs Boon stays on to help with domestic work.

June. Mr Forge, Home Office Inspector, pays us a brief visit.

Disturbance in Senior Dorm at 9.30pm. H and C .....strokes each on seat.

July. B and W abscond. W soon recovered and in consideration of his previous absconding and misbehaviour whilst at Skin Clinic is given 4 strokes on seat with cane.

B brought back from Bristol. 4 strokes on seat with cane.

B. W and S abscond whilst Mr Widgery is taking bath. Commit numerous housebreaking offences at Holne.

3 absconders brought back from Weston Super Mare.

B and S again abscond - actually whilst Police are in the building interviewing the 3 offenders.

Superintendent in touch with police and magistrates' clerk with a view to having B remanded in custody.

[In July a letter appeared in the local paper, which was highly critical of the remand home. Rates were increasing, said the writer, W J Chambers, and yet money was being lavished elsewhere: 'it is alleged that this place provides every device and luxury in the way of games, sports, and means of pleasurable recreation for the fortunate inmates, the latest being a large and expensive rocking horse de luxe for the entertainment of the younger guests. I am told that any child who picks a pocket or robs a till, or indeed shows any criminal tendency is received with open arms at this 'Palace of a thousand delights'.

Mr Thorogood pasted a cutting of the letter into his diary.]

20th July. Amazing letter in local press. Actually the rocking horse and a 'swing boat' were bought at a Newton Abbot sale for 10/- the pair, the purchase being a personal matter and never charged to County.

Another cricket match with local lads. Ashburton 105 for 7 dec. Remand Home 71 for 6.

August. Mr Widgery leaves as holidays commence. Mr Robinson, a School Enquiry Officer, arrives to assist for a week.

Visit of the portreeve, (Mr Brian Baker) and Mr R Andrews. Lads given a very interesting talk on Sicily. Visitors much impressed - we are very pleased as local people have got (?) a poor idea of our work, the kind of life we lead, and our difficulties.

R 2 strokes on hands - laziness and wetting his bed.

Mr Bawery (sp?), who has been appointed as Deputy Superintendent, arrives to take up duties. Mr Robinson leaves

Superintendent, Mr Bawery and 25 boys spend day on Hay Tor and pick 15lbs of whortleberries.

F, 1 stroke on hand with cane - scratching name on lavatory wall.

Mr Thorogood pasted a cutting into his diary, which was the result of his writing to the Education Secretary in November 1943. The Remand Home Management Commitee, at a meeting the same month, decided to recommend that the salaries of the following staff be increased:

Mr G F Thorogood, Superintendent, from £250 per annum, plus war bonds and emoluments, to £270 per annum plus war bonds and emoluments. Automatic increases of £20 per annum were to be implemented, rising to a maximum of £350 per annum.

Mrs O Thorogood, the Matron, from £80 per annum plus emoluments valued at £80 per annum, to £110 per annum plus emoluments, rising to £120 in November 1944.

In January 1944 three hundred raspberry canes were received from Pinhoe Remand Home and planted.

The Remand Home held a boxing tournament in December 1945, the referee being Sergeant Bray RAF.

Mr Thorogood pasted a newspaper cutting into his diary, which spoke of the 'pluck and determination' of the youth of the time. The competition was held in the dining room, in a ring that the boys had made themselves. There were 10 bouts for boys ranging in age between 12 and 16 years of age, and the boxers were presented with savings certificates at the end of the evening.Above: The Superintendent relaxing

To be continued

***