The Wool Trade

The advantages of fast flowing rivers......

The importance of the wool trade to Ashburton can be seen by the inclusion of a teazel in the Town Arms (below) - used for brushing up the surface of cloth during manufacture. In 1956, in a lecture on the West Country Woollen Industry, Mr K G Ponting said that teasel gigs were still used. Another step in the process was fulling, and he described how loose cloth was 'felted together' to make it warm and durable. From at least Roman times people achieved this by massaging it with their hands, or they walked on it. Then the first machine in the wool trade was invented - water drove a wheel, which in turn drove hammers, and these pounded the cloth. Towns with fast flowing rivers then came into their own: although Mr Ponting was speaking about places in Gloucestershire and Dorset, Ashburton would have been amongst them. He went on to say that between 1350 and 1400 the wool industry became the major trade of England.

Lecture on 'The special characteristics of the West Country Woollen Industry', K G Ponting, Director Samuel Salter and Co. Ltd, at the Royal Society of Arts February 1956. Publ by the Dept of Education of the International Wool Secretariat, Regent St., London.

*******

For an account of the wool industry in South Devon in the mid 1850s, see the article in the Western Times 26 January 1850 p8 cols 3,4,5

From Charles Knight's Pictorial Gallery of Arts: Wool: merino sheep, wool processing machinery, and teazle. 1858, Available via Wikimedia Commons

Left: The Town Arms, above the gates to St Andrews' Church

My own photograph 2012

Gifts: '1 sheep the gift of William Denbold besides 1 sheep already in his custody.'

Devon and Cornwall Record Society, Churchwardens Accounts of Ashburton, 1479-1580, Alison Hanham, The Devonshire Press, Torquay 1970, p84

'In 1672, Mr John Ford procured another market, on Tuesdays, chiefly for wool and yarn (spun in Cornwall), but this market has for some years been discontinued'

Ashburton and its Neighbourhood, Charles Worthy, printed and publ by L B Varder, Ashburton 1875 p7

*******

'In some parts of this county considerable attention is paid to the breeding of sheep. The established breed, reared chiefly on Dartmoor and Exmoor, is the middle-woolled class, bearing a strong resemblance to the Dorsets; but many other kinds are also reared. The total stock is estimated at 630,000, nearly 200,000 of which produce heavy fleeces of long wool.'

The Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales 1840, A. Fullarton & Co. Glasgow, Edinburgh and London 1841 p587

"The short, or rather middle-wooled sheep of Devonshire.......have white faces and legs, generally horned but some without horns. They are small in the head and neck, and small in the bone everywhere....The fleece is 3 or 4 lbs in weight in the yolk, and the wool is short, but with a coarse and hairy top...

The wool produced in Devonshire used to be manufactured in the same county, not indeed in large factories, but at home and by the family of the principal workman. This old method of working the wool, never very profitable or consistent with the commercial superiority of England, is now laid aside; but it lingered longest in this south-western portion of the kingdom.

In very few counties in England has so complete an alteration taken place in the character and produce of the sheep as in Devonshire. When Mr Luccock compiled his table in 1800, he stated the number of short-woolled sheep 436,850, and that of the long-woolled sheep 193,750. The number of packs of short wool were 7280, and of long wool 6458 packs. The number of packs of short wool has now diminished to 2275, but no satisfactory account has been obtained in the increase of long wool. The fleece of the Dartmoor sheep, as well as the carcase, has been essentially altered by a cross with the Leicesters....The fleece has...materially improved in fineness and softness of fibre, and is more useful for many important purposes ".

Sheep, their Breeds, Management and Diseases, William Youatt, Orange, Judd and Co., New York, 1867, pp 251,253,254

Right: A Dartmoor sheep. Coloured stipple engraving by James Joshua Neele.

Wellcome Library, London; Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons by-nc 2.0 UK: England & Wales

'The only material used in the South Devon factories is English wool, and generally that of our own county...'

Western Times 26 January 1850 p8 col5

Above and above right: Modern Devon and Cornwall long-woolled sheep.

My own photograph 2013. Thanks to N & N Haley, Forder Flock of Longwools

The yolk is the grease covering the wool - it is produced by the sheep's skin to give the wool water resistance.

http://accidentalmallholder.net/

The price of yolk wool in 1842 was 6½d to 6¾d a pound.

Western Times 15 October 1842 p3 col5

By 1844 yolk wool was 8½d to 9d a pound.

Exeter Flying Post 1 August 1844 p3 col6

The price of yolk wool in 1851 was 7½d a pound. An agreement had just been reached on the price manufacturers would pay woolcombers in the town. This was not the first time that there had been negotiations - the 1842 report above commented that the workshop doors were opening again after being closed for a long time.

Western Times 25 October1851,p7col3

In 1853 the Western Times reported that the price of yolk wool was high, the paper suspecting that the suppliers were holding on to large stocks. Rather than pay the price demanded, many manufacturers were stopping work.

Western Times 26 November 1853 p6 col6

In 1855 yolk wool was at 8½d a pound, but the price was tending to go lower.

Western Times 28 July 1855 p7 col4

In 1858 1s a pound was considered a good price.

Western Times 25 September 1858 p6 col3

By 1872 the price of wool was 1s 5d a pound

Western Times 21 June 1872 p5 col6

In 1884 the price was 6 to 6½d a pound

Western Times 21 January 1884 p3 col3

*******

An Act for Burying in Woollen, 1677*

'Whereas an Act made in the that

now is, intituled, An Act for Burying in Woollen only, was intended for

the lessening the Importation of Linen from beyond the Seas, and the

Encouragement of the Woollen and Paper Manufactures of this Kingdom, had

the same been observed ; (2) but in respect there was not a sufficient

Remedy thereby given for the Discovery and Prosecution of Offences

against the said Law, the same hath hitherto not had the Effect there by

intended :

II. For Remedy whereof..... it is hereby enacted by the

Authority aforesaid That from and after the first Day of August one

thousand six hundred and seventy-eight, no Corps of any Person or

Persons shall be buried in any Shirt, Shift; Sheet or Shroud, or any

thing whatsoever made or mingled with Flax, Hemp, Silk, Hair, Gold or

Silver, or in any Stuff or Thing, other than what is made of Sheeps Wool

only, or be put in any Coffin lined or faced with any sort of Cloth or

Stuff, or any other Thing whatsoever, that is made of any Material but

Sheeps Wool only: (2) upon pain of the Forfeiture of five Pounds of

lawful Money of England, to be recovered and divided as is hereafter in

this Act expressed and directed'.

Copyright Guy Etchells © 2001-2006 All rights reserved.

* 30 Car. II. c.3 This replaced an earlier act of 1666: 18 Car. II. c.4.

The 1677 Act was repealed by the 54 Geo. III, c. 108.

Serge

Serge is a durable cloth with diagonal lines or ridges on both sides (twill weave). Often used in making military uniforms, suits and greatcoats.

http://www.collinsdictionary.com and others

It is made from a long fibre wool combined with a yarn made from a shorter fleece - see Exeter Memories for more detail on this. The website also has Celia Fiennes writing about the wool trade in the south west in 1698

http://www.exetermemories.co.uk

'In the ....arming of 1798 Ashburton had formed the 9th Devon Corps, under Captain Walter Palk; they had clothed themselves with local made serge, and so gained the name of Sergebacks'

The Haytor Volunteers, Lieut-Col Amery, publ Mortimer bros, Totnes, 1888, p17

'Formerly about £100,000 worth of serges were made here* yearly.'

*ie Ashburton.

History, gazetteer and directory of Devonshire, William White 1850, p462.

*******

Philip Foott; John Soper; William Sunter; John Tozer; Richard Tozer; John Winsor; John Caunter; Peter Fabyan; Walter Shellabear.

For more on John Caunter see the Individual Families section.

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk, ref 3768Z/Z/1, xerox copy held by Devon Archives and Local Studies Service

Jan 27 1790 Thomas Soper, sergemaker of Ashburton, Devon, insured with The Royal and Sun Alliance Insurance Group.

Ref CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/366/565653 London Metropolitan Archives http://search.lma.gov.uk - Accessed 20-02-2017

Jan 28 1790 Walter Soper, sergemaker of Ashburton, Devon, insured with the Sun Fire Office.

Ref CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/366/565657 London Metropolitan Archives http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk -Accessed 20-02-2017

Jan 28 1790 John Soper, sergemaker of Ashburton, Devon, insured with The Royal and Sun Alliance Insurance Group.

Ref CLC/B/192/F/001/MS11936/366/565658 London Metropolitan Archives http://search.lma.gov.uk - Accessed 20-02-2017

Ref MS 11936/385/598973

London Metropolitan Archives http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk - Accessed 22-02-2017

All

of the above appear to be connected with Messrs Green and Walford's

warehouse, Little Winchester Street, late Spencers malt lofts, near

Hayes Wharf, Tooley Street.

John Soper, sergemaker, was buried on January 11th 1792

Mrs Soper, widow of John Soper, sergemaker, was buried on February 15th 1795

Parish records

For more on the Soper famliy see the Individual Families section

***

Ref 4289A/PO/3/b/2, Devon Heritage Centre, https://devon-cat.swheritage.org.uk/records/4289A/PO/3/b/20

1783 John Tozer, sergemaker, was buried on April 27th.

Parish register

Some had more than one occupation - for instance, William

Sunter was a maltster as well as a sergemaker; John Tozer was both a

sergemaker and a shopkeeper.

For more details of what was insured see

The Devon Cloth Industry in the Eighteenth century, Sun Fire Office

Inventories of merchants' and manufacturers' property 1726-1770, Edited

by Stanley D Chapman, Devon and Cornwall Record Society, 1978, p1ff

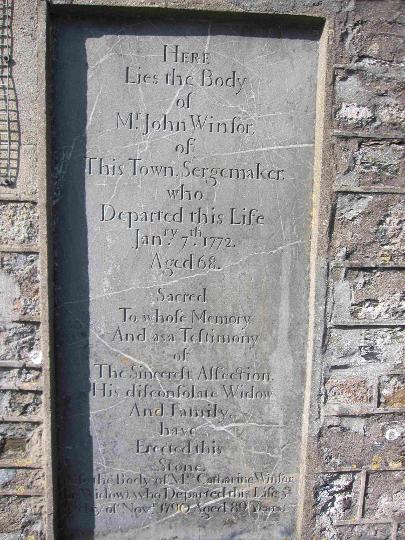

In 1766 John Winsor insured stock in 5 warehouses at Hay's Wharf, Bridge Yard, Southwark, with the Sun Fire Office.

Ibid p2

The memorial also commemorates his wife Catherine, who died in November 1790, aged 89.

Exterior wall St Andrew's Church. My own photograph 2014

'In 1787 295,311 pieces (of woollen cloth) were exported from Exeter. In 1789, the East India trade being then increasing, 121,000 pieces were bought by the East India company alone.

The Parliamentary Gazetteer of England and Wales, A Fullarton and Co., Glasgow, Edinburgh and London, 1841,Vol1, A-D, p587,588

The Devon Archives and Local Studies Service has a lease dated 1788 concerning a messuage, orchard and garden in St Lawrence Lane. William Fabyan ('Now of Plymouth...but heretofore of Ashburton, perukemaker') was one of the parties - he was the only son and heir of George Fabyan, woolcomber, deceased.

Ref Z10/2/5a, Devon Record Office, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk

Bankrupts from the Gazette. December 7 1790. Edward Laskey, of Ashburton, sergemaker.

Universal Magazine, vol 86, London 1790, p366

The steps involved:

Shearing the sheep.

Grading and Sorting. This was done by a wool sorter or stapler.

Colin Waters, A Dictionary of Old Trades, Titles and Occupations, Berkshire 1999

Dyeing (a process that can also be done once the fabric is made).

Carding. Raw wool was raked through to untangle it and make the fibres roughly parallel. Woolcombing was a more thorough process, where in addition to raking, short staple wool was removed. Woolcombing was an apprenticed trade.

Family Tree magazine, November 1996, vol13 no 1

Spinning

Weaving

Cleaning and Scouring. Fullers, also known as tuckers or walkers, cleaned the cloth of dirt and lanolin. In medieval times this was done by treading the cloth in stale urine. The process also closed up the threads of the cloth.

For an entertaining re-enactment of fulling, see Tony Robinson, The Worst Jobs in History https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vb0V5NSgAo0 - Accessed 11-09-2017

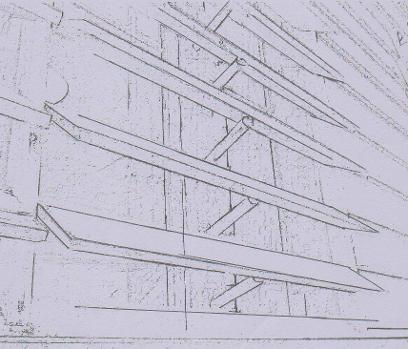

Tentering. The cloth shrank during fulling, so was stretched on frames to re-shape it. It was hooked onto hooks on the frames called tenterhooks, and left to dry and bleach in the sun.

Finishing. Knots, loose threads, plant material etc. were then removed from the cloth using tweezers.

Afterwards the cloth was brushed with teasels, often set in a frame, to raise the nap.

A shearman would shear the nap from the cloth to achieve a smooth finish.

James Burnley, The History of Wool and Woolcombing, London, 1889, is available here:

https://archive.org/details/historywoolandw00burngoog

See also http://www.tuckershall.org.uk/hall/history/processes

The 3rd February is St Blaise's Day, the patron saint of woolcombers.

In 1841 the woolcombers of Ashburton and Buckfastleigh held their annual dinner to commemorate the day.

http://www.catholicculture.org - Accessed 30-07-2014

Western Times 6 February 1841 p3 col3

The book of English trades and library of the useful arts, publ. J. Souter, London 1818

Above: A drying loft, part of the Olde Weavers House, 5 Kingsbridge Lane. This is where wool was dried, or possibly where the serge was stretched on tenterhooks attached to racks - hence the expression 'to be on tenterhooks'. (Red Herrings and White Elephants - The origins of the phrases we use every day, Albert Jack, Metro Publishing Ltd., 2004).

This one can be seen from the carpark - many of the buildings in the Kingsbridge Lane area, some now demolished, were connected to the woollen trade.

Cherry and Pevsner describe No 5 as 'the best surviving example in the town of a c18 wool-weaver's house, with large first-floor windows and weatherboarded top-floor drying loft.

Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Devon, revised ed 1989, New Haven adn London, p133

My own photograph 2013

A wooden upright behind the louvres had pegs attached at regular intervals. When the piece of timber was rotated (probably by means of a handle at the back) the pegs pushed open the louvres.

Thanks to Nigel Irens for this information.

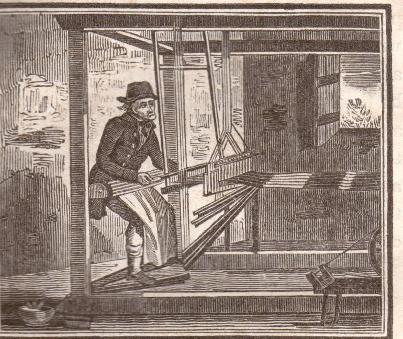

'It is quite unnecessary to distinguish between the silk, the linen, or the Weaver of woollen, etc. The general principles upon which they proceed are the same, and they only differ in the materials they manufacture. The thread is first wound on wooden bobbins, to prepare it for being warped on what is called a mill, by which both the length and breadth of the web is defined, and the threads put in such order that they are in a state to be wrought by the weaver, who shoots the woof across the warp by means of a shuttle, which he throws from right to left, and left to right alternately between the threads, whilst the threads are raised and lowered by the treadles, and every time it is thus thrown, a thread of the wool is inserted in the warp. This he continues to do till the web is finished.'

Artificiana; or a key to the principal trades, Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh, 1819, p 19

Above: Woodcut from Artificiana

Left: Shears, used for trimming the nap on material. They are the width of the fireplace in Tuckers Hall, Exeter (about a metre)

My own photograph 2017. Many thanks to Tuckers Hall http://www.tuckershall.org.uk/

'The introduction of worsted spinning-frames in the North of England early in the present century revolutionised the trade, and in 1817 Mr Caunter started the first worsted spinning-frames in Ashburton, charging 10d a pound for spinning. For a while he held the monopoly...'

A Book of the West, S Baring-Gould, vol 1, (Devon), London 1899, p251

1807 Obituaries. At Ashburton, Devon, aged 99, Mr Hurst, woolstapler.

The Gentleman's Magazine, vol 77, 1807, p1233

In

1817 Solomon Tozer sold his 'substantial' house in West Street. Amongst

other rooms it consisted of two parlours and a drawing room, 7

bedrooms, 'an excellent pump', and drying lofts. It could be used as a

family residence, a boarding school, or, the advertisement suggested,

'the serge trade'.

Exeter Flying Post 16 October 1817 p1 col5

'At an early age' John Sparke Amery, who was born in Lustleigh, came to live with his maternal uncle, Mr P S Sparke*. Mr Sparke was a woollen manufacturer, and when he died in 1843, John S Amery succeeded to the business. 'In 1846, the woollen trade being very much depressed, he retired from business and turned his attention to farming'.

*Should be P F Sparke. See the Sparke and Amery families.

Transactions of the Devonshire Association, vol 10, 1878, p51, available at Full text of "Report & Transactions of the Devonshire Association Vol 10 (1878)"- accessed 02-04-2025

In 1824 The Exeter Flying Post reported the death of John Berry, 'formerly a respectable serge-maker' of Ashburton.

Exeter Flying Post 26 August 1824 p4 col2

1827 The Rew fulling mills and causeway were amongst a large amount of leasehold property up for auction. The Messrs. Caunter were listed as the tenants or occupiers.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 6 January 1827 p1 col3

On December 31st of the same year 'Notice is hereby given that the partnership subsisting between us the undersigned, John Caunter and Richard Caunter, of Ashburton, in the County of Devon, Sergemakers and Woollen Manufacturers, under the firm of J and R Caunter, is this day dissolved by mutual consent...' Richard Caunter was to continue the business.

London Gazette 4 January 1828, Issue I8429, p33

'An article in your paper tells us the East India Company have only contracted for 25,000 pieces of serges; and in consequence of which...the inhabitants of Ashburton are thrown into the greatest distress, and hundreds destitute of the common necessaries of life. About seven years ago the purchases of the East India Company were about 350,000 pieces of long ells annually; these are now reduced to 100,000 or 150,000 pieces...'

The Oriental Herald, vol XX, Jan-March 1829, p217

Exeter Flying Post 19 March 1829 p1 col5

By 1829 John Berry and Richard Bennett Berry, of Ashburton and Ivy-Bridge, Woollen manufacturers, had become bankrupt. The London Gazette advertised that their 'capital mill' was to be auctioned. Suitable for a corn-mill or paper-mill, as well as its current purpose, it had the advantage of a strong water course, which continued even in the driest summer. The mill contained frames for spinning worsted, and machines for spinning yarn.

London Gazette Issue 18564 3 April 1829, p633

'In 1838 there were still in the county 39 woollen mills and more than 3000 looms employed in weaving serges. Of the latter there were in and around Ashburton 660...'

White's History, Gazetteer and Directory of Devon 1850, p44

By 1839

the Western Times reported that 'The trade of Ashburton is much

depressed at present', with high unemployment amongst weavers and

woolcombers* (between 2000 and 3000 in the Ashburton and Buckfastleigh

district, according to the article). Some went as far as Yorkshire

seeking work, but had to return home 'in a very distressed condition'.

Western Times, reported in Palmer's Index to The Times, 3 December 1839, p6 col 3

*Wool combs can be seen in Buckfastleigh Museum, alongside the Valiant Soldier Museum

In 1852 'the extensive woollen manufactory at Buckfast, the property of S Tozer Esq.,' was acquired by John Berry of Ashburton. The machinery would soon be set to work.

Western Times 22 May 1852, p5 col3

In 1898 Mr J Alsop resigned as Clerk to the Newton Board of Guardians. He was appointed to the post in 1840, and remembered just before that time that 50 men arrived at the workhouse seeking relief, having lost their jobs at the Ashburton Serge Factory. People's prospects were so poor at the time that many emigrated to America and the colonies.

East and South Devon Advertiser, 15 January 1898, p8 col2

*******

...Whenever young women are employed who have no domestic occupations to interrupt their weaving, they finish two pieces, or two and a half pieces in a week, for which they are paid 5s to 6s 3d; some of these being orphans, or too old to be longer a burthen to their parents, are maintained only by the produce of the loom, and these persons are generally kept in constant employ, if the state of the trade will permit.'

The Sessional Papers of the House of Lords, 1840, vol 37, p445

In 1841 there was a large amount of serge and wool being stolen in the district. If caught, the offenders faced a hefty penalty - a W MacDowell and W Major had been transported for 14 years after stealing wool from R Caunter. Now W MacDowell's wife, Ann, was giving evidence against four new suspects: Thomas Connibeare, William Westaway, William Harris and John Ayres. William Westaway had escaped custody at one point, but the Town Crier offered £10 reward and he was soon recaptured.

Mischievously, the Western Times reported that the four prisoners had all been supporters of the old political system (ie not reformers), and were stalwarts of the church and state. 'Toryism', the paper said, 'loses in them four good votes'.

Western Times 22 May 1841 p3 col 5

See the Caunter Family under People and Properties for more details of Richard Caunter's premises, which was in the Kingsbridge Lane area.

*******

Wool had traditionally been shipped from Totnes, but by 1844 this had changed. The river charges had increased enormously after improvements to the river Dart, and consequently the woollen manufacturers started sending consignments to Torquay or Teignmouth. The arrival of the railway was anticipated to be a 'great accommodation for the woollen trade.'

Western Times 11 May 1844 p3 col2

********

1847. The Western Times complained at the new postal arrangements. Plymouth and Totnes letters sent in the afternoon were carried to Newton Abbot and left there overnight, so that they did not arrive at Ashburton until the next day. Woollen manufacturers, pointed out the newspaper, depended on the post for orders from their London and Northern markets

Western Times 25 September 1847 p7 col1

*******

1848 A woman named Twiggs fell through a trapdoor in one of the wool lofts belonging to Richard Caunter, in Kingsbridge Lane. She fractured her skull and was not expected to recover.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 28 January 1848 p8 col 2

In 1848 50 men, mainly involved in woollen manufacture, were suffering hardship through unemployment. They petitioned the vicar, the Rev W Marsh, and others, to help alleviate their condition. The wool shops had by this time been closed for some weeks, due to 'stagnation' in the wool trade.

Exeter Flying Post 3 February 1848 p3 col6

In 1849 three poor women were making their way towards Ashburton carrying serges on their backs which they had woven during the week. A Church of England minister travelling in the same direction dismounted and put the serges across the saddle of his horse, which he then led into the town.

Western Times 10 March 1849 p7 col3

The woollen trade that year was dull, but there was a 'fair demand for blankets and serges, principally for the East India and the home markets'.

Exeter Flying Post 7 June 1849 p8 col4

********

In 1854 the extreme dulness of trade resulted in 40 Buckfastleigh people and a number from Ashburton leaving for Quebec. The ships the Rose and the Lady Peel were leaving from Plymouth.

Western Times i1 April 1854 p7 col5

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 28 April 1876 p1 col2

1878 'At Ashburton Messrs Berry alone represent the once numerous body of clothiers, and it is due to their perseverance, and to that of Messrs Hamlyn, of Buckfastleigh, that the branch still exists in the valley of the Dart. Although they have extensive sorting shops etc. within the borough of Ashburton, yet the Messrs Berry do not actually carry on their manufacture within the ancient borough, and a calamitous fire which occurred on the 19th of November 1877, the same that witnessed the similar destruction of Lamerton Church, burnt to the ground their largest mill, which was situated at Buckfast, and which was a very extensive erection of five storeys, and filled with the newest and best machinery.'

History, Gazetteer and Directory of Devon, William White, Sheffield 1878-79, p36

There were labour troubles in 1891, after some workers in the woollen industry had joined the National Union of Gasworkers and General Labourers; however, the workers at the Ashburton mill, around 90 in number, 'held aloof'. Messrs Berry and Sons of Ashburton and Buckfast said that they had hesitated to interfere, but that the union members, 'with taunts and jeers' were trying to force non-unionists to join them. Consequently the owners warned that they would not employ union members: people had freedom to join a union, but they had the right to employ whoever they wished.

The dispute was mainly about unionism, but there were other issues. Many workers lived in Ashburton, but worked in Buckfast, and had a two and a half mile walk there and back. This affected the number of hours that a pieceworker could work. The question of wages had also been raised. At the time sorters and wool pickers (young women) eamed 9s a week. Dayworkers aged 14 and over, mainly females, earned 7s - 10s a week. Weavers, mainly females but some young men, earned 9s - 21s. Youths above 17 and men earned 12s - 26s.

The paper pointed out that the work was continual, and the wages regular.

Western Morning News 3 December 1891 p5 col5

'Lockout of 300 hands imminent'

Column heading, Western Morning News 4 December 1891 p3 col2

On December 11th, as the notice period expired, about 70 weavers left the Buckfast premises, leaving around 40 still at work. The absence of the weavers would affect all the other processes at the mills. It was difficult to estimate the number of other workers who were leaving, but it appeared to be a majority.

Wagonettes were used to transport the non-unionists to and from Ashburton - one evening the wagonettes had to drive through a large crowd of people thronging the Bullring and the streets. 'There was considerable hooting on the part of the crowd.'

Western Times 11 December 1891 p8 col4

Western Morning News 15 December 1891 p3 col3

By March 1892 Messrs Berry and Sons were taking on new workers. During a meeting held by Unionist leaders outside the Buckfast works a fight broke out: one woman fainted, and one man was bleeding profusely. The police were called and the crowd dispersed.

Western Morning News 14 March 1892 p5 col3

There was no sign of settlement in April - the mills were still working, but at a reduced rate. The Western Morning News stated that the Ashburton locked-out workers 'kept excellent order, and have given no trouble.' By May the dispute was said to be on the brink of collapse, and on the 25th May the Western Times reported that an amicable solution had been reached. Messrs Berry and Sons stated that they were willing to take back locked-out workers as non-union members. Mr Gardner, the union representative, left by the afternoon train.

Western Morning News 13 April 1892 p3 col1

Totnes Weekly Times 7 May 1892 p5 col2

Western Times 25 May 1892 p3 col5

Mr J W Gardner giving evidence to the Royal Commission on Labour in August 1892: 'Mr Berry himself has told me in a private conversation on the Ashburton Road: "I must admit that in the past we have not paid the wages that we ought to have done. But," he said, "we have paid the same wages as other people in the trade." He said, " I admit that women walking from Ashburton to Buckfast, two miles and a half each way, that is walking two and a half miles in the morning and two and a half miles at night, for 7s a week is not right - that is not wages enough." ', London

1841 Witnesses in the case where William Barnes was accused of stealing wool from Richard Caunter:

William Burge, woolstapler, worked in the inner sorting room.

James Badcock, a woolcomber

Joseph Mugford, a wool sorter.

Western Times 27 February 1841 p3 col5

The 1841 census shows Samuel Wills, a woolsorter, living with his wife and daughter in North Street. In the same building is James Wills, also a woolsorter.

1841 census HO 107/253/3 11 15, Ashburton, North St. See The Wills and Eales family under Individual families for more on Samuel and his descendants

See Roll of Honour WW1, entry for Sidney Bowden

David Bowden in 1901 is living in North Street and is employed as a mule minder* in a woollen factory.

See Roll of Honour WW1, entry for David John Bowden

See Roll of Honour WW1, entry for Daniel German

The 1911 census for Ashburton records the Baker family living in North Street, with head of house Alfred 41 years old and employed as a wool dyer.

See Roll of Honour WW1, entry for Sidney Baker

The Chivall family have moved to North Street by 1911. Evelyn aged 13 is employed as a wool sorter.

See Roll of Honour WW1, entry for Simon Garfield Chivall

The

1911 census shows Alfred Eales living in Craig's Corner, Kingsbridge

Lane, Ashburton, in the residence of William Thorne. Alfred is aged 18

and employed as a woollen mule pieces (sic - probably piecer). **

See Roll of Honour WW1, entry for Alfred Eales

*Mule minders watched over the spinning mules.

**Mule piecers leaned over the spinnimg mules to tie broken threads together.

http://www.weasteheritagetrail.co.uk/Resources/some-old-job-titles-from-the-textile-industries/index.htm

http://www.powerinthelandscape.co.uk/education - Both accessed 3-11-2015

*******

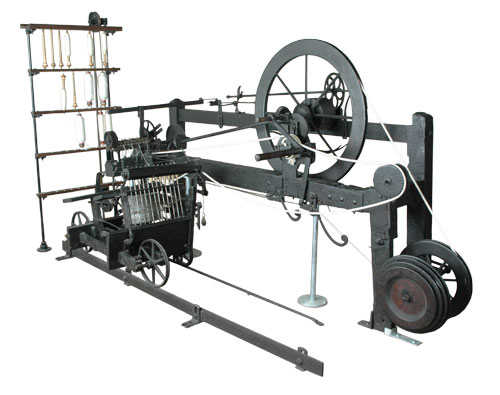

The Spinning Jenny was invented by James Hargreaves in 1764 - a spinner turning a wheel by hand could draw out and twist several threads at once. In 1769 Richard Arkwright invented a water frame, which was driven by water power and squashed and stretched the yarn. Samuel Crompton combined the moving carriage of the Spinning Jenny with the rollers of Arkwright's water frame, and developed the Spinning Mule (called mule because it was a cross between two different 'animals'). This machine allowed greater control of the weaving process, and could produce a variety of yarn. Each carriage carried 1320 spindles and was up to 46m long, and the carriage moved back and forth 1.5m four times a minute. On the early machines yarn had to be wound onto the spindles by hand, but later this was done automatically - a 'self-acting' mule.

http://www.newlanark.org/uploads/Spinning%20Mule.pdf

http://www.intriguing-history.com/was-spinning-mule

http://www.boltonmuseums.org.uk - All accessed 2-11-2015

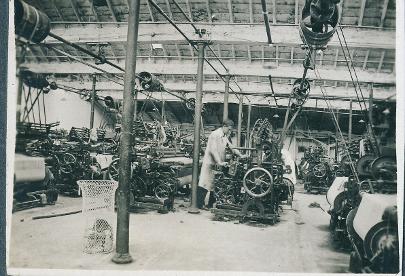

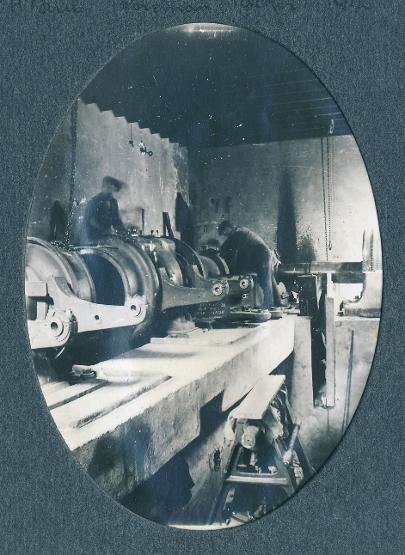

Many thanks to Lerida Arnold for these photographs

Above: Foreground - a monument to the Berry family in St Andrew's churchyard, which includes the following inscription: 'In loving memory of John Berry, woollen manufacturer of this town. Died March 27th 1889, aged 59 years'.

In his memories of growing up in Ashburton John Satterly, born in 1879, says that by the end of the 19th century most of the operations connected to the wool trade had moved to nearby Buckfast.

John Berry's mill had moved from North Street, but there were still offices and sorting sheds in the vicinity of Kingsbridge Lane. Buyers would go out to the farms to buy the wool, weighing it on a steel yard to calculate what would be paid. Back in Ashburton the wool was sorted, cleaned and packed into large bags - these were lowered by pulley onto the carts that would then take them on to Buckfast.

William Edmonds, a woolcomber of Kingsbridge House, gave evidence, and said that the accident occurred as they were packing wool. A bag was suspended from a beam by two ropes, which the deceased had tied, before getting into the bag to tread down the wool to pack it tighter. A rope slipped, one side of the bag collapsed and Mr Smerdon fell about 4'6" to the stone floor, landing on his head. Although conscious, he had fractured his spine.

Mr C H Baker, foreman of the jury, questioned whether this manner of working was safe, and Mr Edmonds replied that it had always been done this way. Another witness said there had been accidents before, but nothing serious, and he did not know of a safer way of performing the task. There was a safety rope in the centre of the bag, and it was concluded that the deceased must have let go of it.

A verdict of Accidental Death was returned, with no-one to blame.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 31 January 1928, p2 col3

*******

Other Mills

In 1847 there was danger of a riot in Ashburton because of the high price of corn. A large number of men (mainly, according to the newspaper report, miners), women and children gathered near the Mr W R Whiteway's Town Mills, which may have been in West St (see below) or may have been in North St., which were also called the Town Mills*. The mob searched through the mill store-rooms, and then '100' women seized a quantity of wheat that was arriving at the yard.

Taking the key to the market from Mr S Mann (and allegedly threatening to break his shop windows if he did not give it to them), the women sold the wheat at 8s a bushel.

The town was in 'a state of excitement' all day, and '200 special constables were sworn in'.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 22 May 1847 p8 col3

*On the 1851 census, which is difficult to read, William R Whiteway, his wife Elizabeth and son William R Jnr appear to be living in Kingsbridge Lane. William senior is a land agent, maltster and (?) seedsman. Robert Osmond, and his brother Alexander, are millers at the 'West Street Mills'.

http://ancestry.co.uk

Western Times 27 September 1851 p1 col3

A few months later another flour mill, the Town and Manor Mills, was being let, as Stephen Yolland was about to give up the business. Only built a few years before, the mill had a 22 foot high water-wheel driven by the river Yeo, 'working three pair stones, flour rubble and smut machines'. A house and a two meadow acre were included.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 13 December 1851, p1 col1

Western Times 9 February 1866 p1 col2

Nicholas Addems and family, Iron Mill, North St

John Knapman and family, Belford Mill

Joseph Holland and family, Ledgecombe*

John Churchward and family, Lemonford Mill**

John Maddock and family, Church Lane

Robert R Osmond and family, Town Mills (West St., 2 properties on from London Inn

William Underhill and family, Fursleigh Mill

*More usually spelled Lurgecombe

**2 members of the family are transcribed as Churchmore

http://www.freecen.org.uk/cgi/search.pl

* ********

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 31 May 1878 p4 col2

The mill was situated behind the Methodist Church in West St., in the area now known as Mill Path. It can be accessed through the alleyway between nos. 7 and 9 West Street.

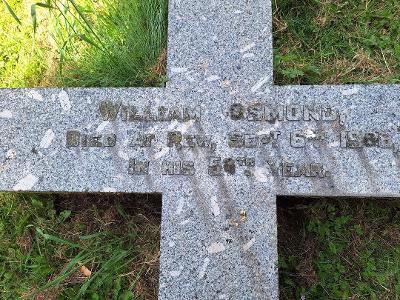

In the 1881 census, William Osmond, a twenty four year old miller, is living in the West Street area with his widowed mother Agnes.

1881 census RG11, piece no 2161, folio 68, p11

to divert all water down the leat, to power the mills. Conversely, the gate on the right could be shut, diverting all water down the river. In the photograph both are open.

Memories of Ashburton in Late Victorian Times, John Satterly, Reports and Transactions of the Devonshire Association, 1952 p35

My own photograph

John Leaman is the miller at the Town Mill in 1901, in the West Street area.

1901 census RG13, piece no. 2053, folio 10, p11

Below left and below: The leat leading to the mill. The picture on the left is looking towards the mill, the one on the right is looking towards West Street.

My own photograph 2016

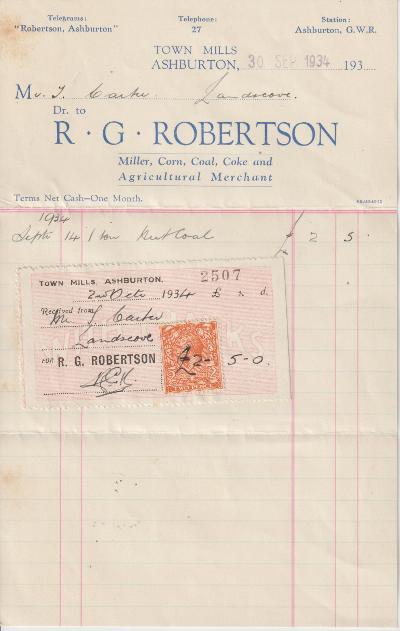

1935 A case was heard in the Chancery Division where four Ashburton mill owners sued Ashburton Urban Council for damages. They alleged that the council had wrongfully abstracted water from the river Yeo (now called the Ashburn), affecting the efficiency of their mills.

James Stephens, Jas. Wm. Redvers Stephens and Ernest Bryant were the owners and occupiers of the Town Mills, North Street, and Mrs. Annie Violetta Taxworth was the owner of the Town Mills, West Street. Although the hearing was adjourned, Mr. Justice Bennett commented on the 'terrible example' of a public authority.

Western Morning News 5 July 1935 p5 col4

********

1938. Kenneth Edward James Harris worked at the Ashburton Paper Mills, earning £2 a week.

Mr Harris was charged with grievous bodily harm - see the Crime and punishment section of Ashburton in Peril.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 4 February 1938 p2 col6

********