Famous Ashburtonians

William Gifford

Above: William Gifford, reproduced from http://www.rc.umd.edu/reference/qr/features/gallery/gallery.html - Accessed 4-11-2013

In the public domain

According to the Family Search website, on 3rd September 1750 Edward Gifford married Elizabeth Cain at Ashburton. The marriage produced two children: William (Gafford) baptised 15th April 1756, mother Eliz, and Robert Gifford baptised 24th April 1764, mother Eliza.

In their biography of William Gifford, B B Edwards and S G Bulfinch say the following: 'His father was a seaman – his manner of life was very dissipated. An attempt to excite a riot in a Methodist Chapel was the occasion of his being compelled to flee the country. His mother was the daughter of a carpenter. She received the rent from 3 or 4 small fields belonging to her husband's father.'

They quote Gifford:

“With these however, she did what she could for me, and as soon as I was old enough to be trusted out of her sight, sent me to a schoolmistress of the name of Parrett, from whom, in due time, I learned to read. I cannot boast much of my acquisitions at this school; they consisted merely of the contents of 'The child's spelling book'.”

At about 8 years old William attended the Free School “Making most wretched progress”.

Both parents died before William's thirteenth birthday. Of his mother he said:

“She was an excellent woman, bore my father's infirmities with patience and good humour, loved her children dearly and died at last, exhausted with anxiety and grief, more on their account than on her own......I was not quite thirteen when this happened; my little brother was hardly two; and we had not a relation nor friend in the world.”

William's brother was sent to the workhouse, whilst he went to the house of his godfather, Carlile. At first he worked as a ploughboy, but then he joined a coaster at Brixham. He was "a little more than thirteen.......it will be easily conceived that my life was a life of hardship. I was not only a ship-boy on 'the high and giddy mast' but also in the cabin, where every menial office fell to my lot. “

He now had no connection with Ashburton, where his godfather lived. But the “women of Brixham, who travelled to Ashburton twice a week with fish, and who had known my parents, did not see me without kind concern, running about the beach in a ragged jacket and trowsers.”

Public pressure became so great that his godfather at last felt obliged to send for him.

“After the holidays I returned to my darling pursuit – arithmetic; my progress was now so rapid that in a few months I was at the head of the school, and qualified to assist my master, Mr E Furlong.*"

He had a plan to become a schoolmaster**, an idea treated with contempt by Carlile.

He “told me....that I had learned enough....he added that he had been negotiating with his cousin, a shoemaker of some respectability, who had liberally agreed to take me, without fee, as an apprentice. “ He was bound to new master 1st January 1772.

“I hated my new profession with a perfect hatred....I made no progress in it.......

........I had not a farthing on earth, nor a friend to give me one; pen, ink and paper therefore were for the most part as completely out of my reach as a crown and sceptre.”

Gifford started to write poetry, and began to get known. “Little collections were now and then made, and I have received sixpence in an evening. ....I only had recourse to it when I wanted money for my mathematical pursuits.”

William was then discovered by William Cookesley, a local surgeon. One of his poems consisted of 'some lines written in ridicule of a wretched painting of a sign of a Rose and Crown, by a carpenter'.

The Selector or Cornish magazine, printed for J. Philp, bookseller, vol 1, Falmouth, 1826, p189

He distributed his verses, and began to raise money for the young man. He raised: “A subscription for purchasing the remainder of the time of William Gifford, and for enabling him for improving himself in writing and English grammar.”

With Cookesley's help he went to Exeter College, Oxford, and after travels on the continent he settled in London. His mathematical pursuits gave way to literary ones, and his fame is as a satirist, translator and critic. He is probably best known for becoming the first editor of the Quarterly review in 1809. He 'rapidly became the best-known Tory polemicist of his day'. (http://www.quarterly-review.org/ - Accessed 1-12-2013. Unfortunately they say he was born in Derbyshire)

Professor Kathryn Sutherland, of the English language and literature facility at Oxford University, has discovered that Gifford read and promoted Jane Austen's novels, including Mansfield Park, Emma, and Pride and Prejudice. In 1815 he wrote to the publisher John Murray, who was thinking of acquiring the rights to the first two: 'I have read the Novel, and like it much...... if you can procure it, it will certainly sell well.'

However, he had reservations about the style: 'It is very carelessly copied, though the handwriting is excellently plain, and there are many short omissions which must be inserted. I will readily correct the proof for you, and may do it a little good here & there.'

The Guardian 23 October 2010 http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/oct/23/jane-austen-poor-punctuation-kathryn-sutherland Accessed 6-3-2014

William Gifford died in 1826, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Biography of self-taught men: with an introductory essay, B B Edwards and S G Bulfinch, Boston, J E Tilton and Company, 1859, pp 110 - 120

* The Rev E Furlong was headmaster of Ashburton Grammar School c 1770 - 1788. Ashburton Grammar School, 1314 - 1938, W S Graf, printed S T Elson, Ashburton, p63.

* *" I might possibly succeed Mr Hugh Smerdon." ibid. Graf says Hugh Smerdon was the master of the Bourne (ie Free) School.

The will of William Gifford

Most of his fortune was left to the Rev Cookesley.

The remaining lease of his house in James Street and a legacy went to Mrs Hoppner, widow of the portrait painter, together with legacies to her daughters.

The poor of Ashburton were to receive the annual interest on a sum of money.

An annual scholarship was founded at Exeter College.

£3000 went to the relatives of his deceased maidservant.

Mr Heber was left any books that he wished to select.

Mr Murray, the bookseller, was left £100.

300 guineas went to reimburse a military gentleman (this appears to be some sort of loan agreement)

Dr Ireland was left 50 guineas and a choice of books

Mr Gifford requested his executors to destroy all confidential papers.

The Examiner 18 February 1827 p11 col1

"While the late Mr. Gifford was at Ashburton he contracted an acquaintance with a family of that place, consisting of females somewhat advanced in age. On one occasion he ventured on the perilous exploit of drinking tea with these elderly ladies. After having swallowed his usual allowance of tea, he found, in spite of his remonstrances to the contrary, that his hostess would by no means suffer him to give up, but persisted in making him drink a most incredible quantity. 'At last,' said Gifford in telling the story, 'being really overflooded with tea, I put down my fourteenth cup, and exclaimed with an air of resolution, 'I neither can nor will drink any more.' The hostess then seeing that she had forced more down my throat than I liked began to apologise, and added, 'But dear Mr. Gifford, as you didn't put your spoon across your cup, I supposed that your refusals were nothing but good manners.' "

The Atheneum; or Spirit of the English magazines, Vol25, April-October 1829, p87

********

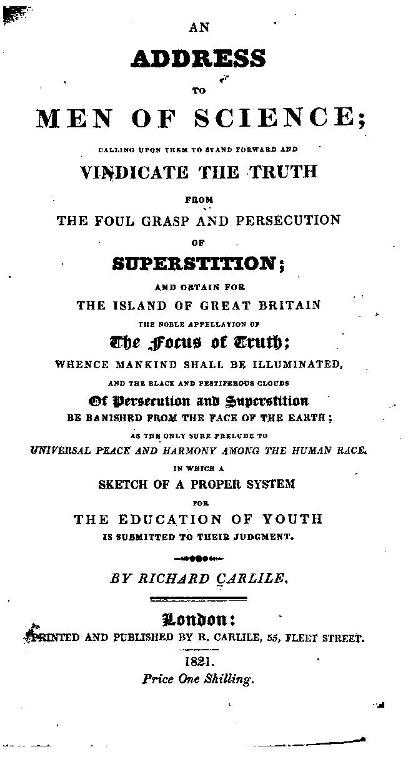

'Free discussion is the only necessary Constitution..'

Richard Carlile, The Republican 1823. Quoted in http://politicalquotes.org - Accessed 24-11-2013

The surnames of Ashburton 'giants': Stapledon, Dunning, Gifford and Ireland have all been used in various combinations as the names of 'houses' in local schools, such as the Wilderness School and the County Secondary School. As far as I am aware, the name of Carlile has always been notably absent.

1899 'We who rejoice in a Free Press to-day can hardly realise the condition of the Press in Europe at the opening of the nineteenth century. In England, eighty years ago, he who dared to express opinions in opposition to the Established Church, or in any way offensive to the government of the day, rendered himself liable to heavy fines and severe imprisonment........he, therefore, resolved to raise the standard of an absolutely Free Press...........This he knew involved possibilities of imprisonment, of exile, losses and suffering.'

The battle for the press, as told in the story of the life of Richard Carlile, Theophila Carlile Campbell (his daughter), London 1899, chapter 1 http://www.gutenberg.org - Accessed 17-11-2013

* as Richard Carlisle

Parish records

BTs

For more of Richard Carlile's memories of his childhood, see Growing up in the 1700s, in the sub-menu of Growing up in Ashburton.

Having worked with a chemist and druggist for four months, Carlile then spent a short time in his mother's shop, where he drew and coloured pictures to sell. He then agreed to become apprenticed to a tin-smith for seven years.

'The work was hard and the hours very long—fifteen or sixteen hours a day—the food was neither good nor plentiful, nor was his master an agreeable one in any respect...... later this same man put himself to considerable trouble, unasked, to go to London from Exeter, and testify to the excellent moral and personal character of his former apprentice, at which Carlile was pleasantly surprised. He often asserted that after such an apprenticeship as he had experienced for seven years, imprisonment was no punishment.....

..."My first attraction to politics was in 1816, in consequence of the general distress then prevalent and the noise made at public meetings. Then for the first time I began to read the Examiner, News, and independent 'Whig' papers. I was pleased with their general tone, but thought they did not go far enough with it." '

ibid, chapter 2

In the public domain.

From

1817 onwards Carlile was arrested and imprisoned several times for

printing various publications, including Thomas Paine's Age of Reason*,

a pamphlet challenging divine revelation and institutionalized

religion.

'On the 16th day of January, 1819, he was informed that The Society for the Suppression of Vice had presented a bill to the Grand Jury, then sitting at the Old Bailey, on a charge of blasphemous libel for the publication of Thomas Paine's theological works.'

ibid, chapter 4

*Part 3 is available to read for free through http://books.google.co.uk - Accessed 25-11-2013. The title page says that it is printed and published by R Carlile in 1818, 183 Fleet Street

In February a Mr Waithman presented a petition from Richard Carlile to the House of Commons, saying that he had been 'unjustly and vexatiously arrested' and committed to prison.

The Examiner, 1 March 1819 p 6 col2

Carlile appeared at the Court of King's Bench in October, facing eleven counts for printing and publishing a libel on the Holy Bible. The first count described him as a 'wicked, impious and ill-disposed person.'

The jury shuddered at many of the passages.

In his defence he read and commented on the Age of Reason for eleven hours, until ten o'clock at night. The Chief Justice then adjourned, saying that he would allow Carlile to continue the next day.

Carlile had subpoenaed the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had to remain in court all day 'and endure the mortificiation of all that passed.'

The Examiner 17 October 1819 p11 col2

Stamford Mercury 15 October 1819 p2 col2

Carlile was found guilty, a verdict that was received with 'profound silence.' The following day a second trial began, accusing him of publishing a libel, Palmer's Principles of Nature

Bury and Norwich Post 20 October 1819 p4 col4

On 16th November 1819 Carlile was sentenced, having been found guilty for both libels. Asked if he wished to say anything in mitigation, he said that he did not, but that he had a lot to say about why he should not be punished at all. He then spoke 'at considerable length.'

For the first offence he was gaoled in Dorchester gaol for two years, with a fine of £1000; for the second offence he was fined £500, and gaoled for a further year. He was only to be released when he paid a further £1000, plus two sureties of £100, to ensure his good behaviour for the rest of his natural life.

Westmorland Gazette 20 November 1819 p2 col3

To pay Richard Carlile's fine of £1000, sheriffs seized many of the items from his house. However, they were wary of selling many of the publications they found there, believing them to be libellous, and instead put them into storage. In 1822 Richard took one of the sheriffs to court, claiming for loss and injury. The jury found for the plaintiff.

Morning Post 3 December 1822 p1 cols1,2

'....Carlile was informed that it was Lord Castlereagh, the then Prime Minister, who was so determined to crush him, and also that it was his publication of the horrors of the Manchester massacre* and his open letters to the King and Lord Sidmouth that gave the offence.....

The charge of blasphemous libel was decided upon, after much consultation, as the strongest that could be brought to bear upon Carlile, as in that case the help and strength of the Church could be had, and the minds of the people could be turned from the contemplation of that bloody affair at Manchester.....'

'Chief amongst his publications were the fourteen volumes of the Republican, a weekly paper of thirty-two pages, ten or more volumes of which were edited in Dorchester Gaol........It was said of the Republican that the only section of the British Press which could be said to be free at that time, was that which was issued from Dorchester Prison.

The names of the various publications brought out by Carlile indicated in a measure the attitude he assumed. They were the Republican, the Deist, the Moralist, the Lion, the Prompter, the Gauntlet, the Christian Warrior, the Phoenix, the Scourge, and the Church.'

The battle for the press, as told in the story of the life of Richard Carlile, Theophila Carlile Campbell (his daughter), London 1899, chapter 1 http://www.gutenberg.org - Accessed 17-11-2013

*The 'Peterloo Massacre' of August 16th 1819. For more see:

http://www.peterloomassacre.org/history.html - Accessed 19-11-2013

An extract from The Republican:

'Mr Sanders'* pamphlet is a catch-penny religious tract, printed in the town of my birth and thrust into the faces of all those of my friends who are espousing the opinions I promulgate. It is not only silly, but in many parts abominably dishonest. I have long entertained the idea of giving the inhabitants of Ashburton, in a distinct address, full and fair reasons for advocating those opinions of which I exhibited so little a prospect when amongst them; perhaps I may address my old acquaintance Tom Morrish, the standing constable, or his brother law officer Robert Palk, the Justice, who, I am informed, threaten vengeance to any person found selling my publication in that very moral and very religious town! From my knowledge of both Justice and Constable I can assert that neither of them knew anything of Christianity, or Deism, or Atheism or Religion, or Morals or Politics when I left Ashburton, but a great deal about ale, cards, pop, skittles and wenches; and I am quite at a loss to know, who or what has inspired them with a knowledge or an abhorrence of the one or the other..'

*Joseph Sanders was a Methodist minister. See Churches and Memorials.

The Republican Vol 9, 1824, R. Carlile, 84 Fleet Street, p74

As Richard had been in the King's Bench prison at the time, having been unable to raise bail, it was ruled that the charge should be brought against Jane only.

She appeared in court with an infant in her arms, and pleaded Not Guilty.

Caledonian Mercury 31 January 1820 p2 col4

* Possibly Jane Consons - Richard Carlisle married Jane Consons 24 May 1813 Alverstoke, Hampshire. https://familysearch.org/search The battle for the press, Chapter 2, says that Jane came from Gosport, now contiguous with Alverstoke.

**Under the title 'A Mock Trial.'

Jane was found guilty and in February 1821 was sentenced to two years in Dorchester jail. On her release she had to find two sureties of £100 each.

Stamford Mercury 27 October 1820 p2 col4

Westmorland Gazette 17 February 1821 p4 col3

In 1821 Richard's sister Mary Ann Carlile was convicted of publishing Paine's Age of Reason. At the Court of the King's Bench she was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment in Dorchester Gaol. She also had to pay a fine of £500, and after imprisonment had to provide security for her good behaviour for seven years: £1000 coming from herself, and two sureties of £500 each.

Northampton Mercury 17 November 1821 p2 col2

Cobbett's Weekly Political Register called The Times an 'execrable paper' for its 'brutal attack' on Mary Ann.

Cobbett's Weekly Political Register 4 August 1821 p25

Both Richard's and Mary Ann's prison sentence ended in November 1822, but neither was released because their fines remained unpaid. But the Morning Chronicle was able to report that 'some persons' had leased a house in Fleet Street near St Bride's Church. They intended to rent this to Richard so that he could carry on in business.

Morning Chronicle 3 September 1823 p3 col4

Freely available through Google Books at https://books.google.co.uk

Carlile was

finally released in November 1825. Most newspapers, including the

Exeter Flying Post, carried a two line statement that warrants had been

sent to the keeper of Dorchester Gaol, allowing him to be liberated.

Exeter Flying Post 24 November 1825 p3 col3

In 1826 he was in trouble again. William Cobbett was outraged that Richard Carlile could suggest that the wives and daughters of the working classes could 'indulge' themselves, both within and outside marriage, without the 'inconveniences....of being mothers.'

Cobbett's Weekly Political Register 15 April 1826 p5

The source of this outrage was 'Every woman's book; or, what is love?' which is both a sex manual and the first book in English to specify means of contraception.The full title continues, 'Containing most important instructions for the prudent regulation of the principle of love, and the number of a family.'

At the end of 1830 Carlile was charged again, with encouraging, by means of books and pamphlets, sedition and rebellion amongst the King's subjects.

In early 1831 he was found guilty and imprisoned for two years, with a fine imposed of £200. On release he was to provide sureties for his good behaviour for 10 years: £500 on his own account, plus two others of £250 each.

Western Times 18 December 1830 p4 col6

Morning Chronicle 12 January 1831 p4 col5

In 1833 5000 people petitioned the House of Commons for his release, and by August he was free. Although originally he was to provide sureties for good behaviour, in the end he was released unconditionally. The London Standard stated that he had then served a total of nine years' imprisonment.

Chester Chronicle 28 June 1833 p4 col6

London Standard 20 August 1833 p4 col4

In 1834 the Morning Post reported that Mr Carlile had (again) put effigies of a Bishop ('Spiritual Broker') and a 'Temporal Broker' in the first floor windows of his house in Fleet Street. Crowds stopping to look at the figures were causing congestion. The room behind the windows was empty - according to the paper this was to indicate that the furniture had all been seized to pay Church rates.*

Morning Post 27 October 1834 p1 col5

*Leading up to this date several papers including the Morning Chronicle 23 October 1834 p4 col5 carried reports of warrants arising from Carlile's refusal to pay the rates of St Dunstan's.

'We hoisted them full length on Sunday, and made the Bishop preach on the present state of the Church to all passers by, from eight o'clock in the morning until six in the evening, while the temporal broker officiated as clerk and published other notices. I very much respect the institution of the Sabbath, and never call on my shopmen to open on that day; but one of them requested that he might be allowed to open, and did so. He retailed seven hundred copies of A Scourge over the counter, beside many other things. Thinking of the matter, I could not but consider it as doing more good than is done by an open gin-shop on that day.........

.......They have been partially exhibited on every other day; but Sunday is to be the grand gala day of public appearance, when the bishop is to have clean boots and clean linen; while the temporal broker must be content to remain as he is, as not worth repair.'

Richard Carlile, quoted at his trial, 24 November 1834

http://www.oldbaileyonline.org version 7.1 Accessed 7-12-2013

By December he had been indicted at the Central Criminal Court for a 'misdemeanour' - displaying the two effigies, plus one of the devil, and causing obstruction of the highway, and annoyance to his neighbours. He was found guilty, but the judge said the penalty would be light providing he removed the figures.

The Examiner 7 December 1834 p11 col1

The judgement was that Carlile should pay a fine of 40s and provide sureties for good behaviour. He was imprisoned in Newgate until these were paid.

However, he soon announced that he had no intention of providing the sureties, and would instead stay in prison for 3 years. The effigies were to be displayed every Sunday.

Morning Post 18 December 1834 p4 col5

Exeter Flying Post 25 December 1834 p2 col1

Carlile suffered ill health for some years, and lived in straightened circumstances. His views, both political and religious became more moderate towards the end of his life, but he was still able to say that 'His life was one continued struggle for truth, and mental and physical liberty, and that his conscience approved his efforts'.

He died on the 10th February 1843.

The London Standard called him 'This man', the Morning Post 'This eccentric man' and the Cork Examiner 'This extraordinary man'. Other descriptions ranged from 'celebrated' to 'notorious'.

His body was dissected for anatomical purposes, at his own request.

Reading Mercury 11 February 1843 p3 col1

London Standard 11 February 1843 p3 col5

Morning Post 14 February 1843 p6 col5

Cork Examiner 15 February 1843 p4 col6

Western Times 18 February 1843 p3 col6

Essex Standard 17 February 1843 p4 col4

The Northern Star was one of the first to assess his legacy. In a lengthy tribute, the paper states 'To him we mainly owe the comparative liberty of the press that we enjoy.'

Northern Star 18 February 1843 p8 col3

But Richard had not yet finished with controversy. When his body arrived at Kensal Green Cemetery, one of his sons told the officiating clergy that they did not want a burial service ('priestcraft') for their father. The clergyman, the Reverend Josiah Twigger, said that he must do his duty, at which point another son objected that they had bought the plot and did not want the service read. In the end the reverend did read the service, but the friends and relatives of Mr Carlile retreated into the mourning coaches and would not listen to it.

The Bury and Norwich Post was puzzled as to why the reverend felt obliged to perform the ceremony. It was equally perplexed at to why the relatives had not had Richard buried in unconsecrated ground.

Bury and Norwich Post 1 March 1843 p3 col1

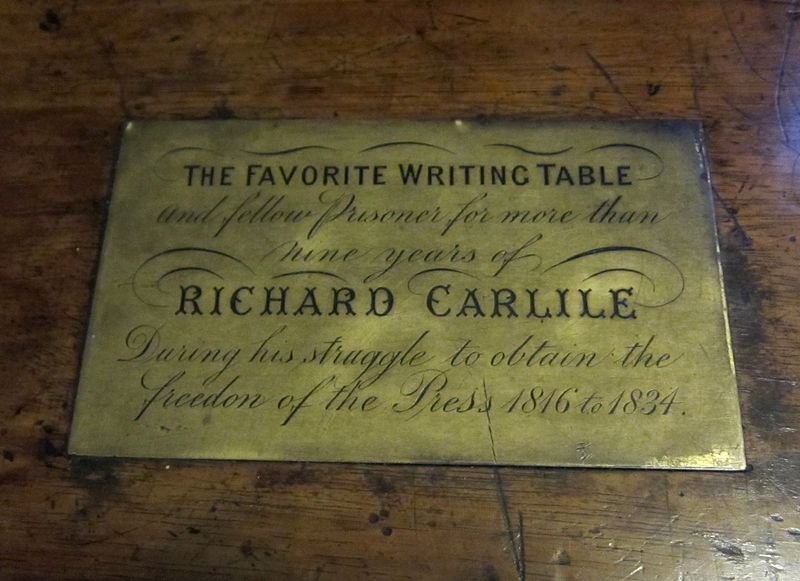

Left: Photo of the plaque on Richard Carlile's writing table in the library of the South Place Ethical Society at Conway Hall. It says ' The favorite writing table and fellow prisoner for more than nine years of Richard Carlile during his struggle to obtain the freedom of the Press 1816 to 1834.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License. Accessed on Wikipedia 8-12-2013

*******

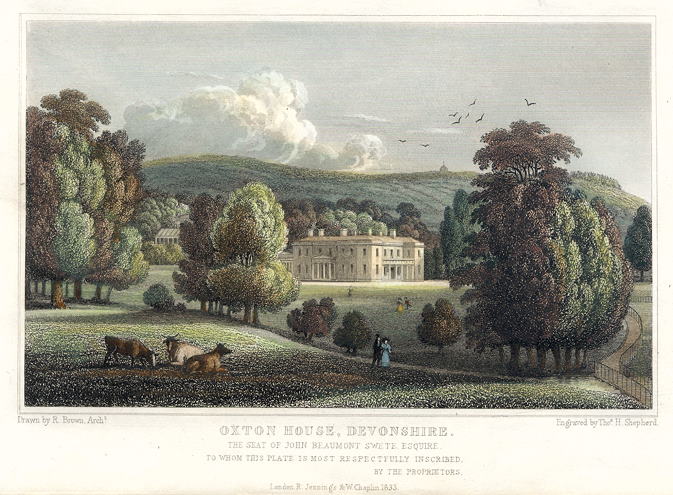

John Swete was baptised John Tripe on the 13th August 1752 at Ashburton, the son of Nicholas and Rebecca Tripe. His father, Nicholas, was a noted surgeon in the town - see the Doctors and surgeons section under Banks and businesses.

https://familysearch.org/

In his 1795 autobiography, 'A Sketch of My Life' he wrote that he was born in July, and that his mother before her marriage was Rebecca Yard. His former home had by then become the Golden Lion Hotel.

Devon Record Office Z19/3/1, reference given in Travels in Georgian Devon - see below.

Colcombe Castle, Rev John Swete, 1795

From http://commons.wikimedia.org/, in the public domain- Accessed 2-6-2014

Mr Smerdon, and then his son the Rev Thomas Smerdon taught him at the Ashburton Free School; Sir Robert Palk helped him to get to Eton in 1769, and from there he went to Oxford. He took Holy Orders in 1781.

Travels in Georgian Devon, the Illustrated Journals of the Reverend John Swete (1789-1800), Todd Gray and Margery Rowe, Editors, Devon Books 1997, vol 1 pp vii foll.

He changed his name as the result of an inheritance:

'I give and devise my said plantation lands, negroes and hereditaments in the said Island of Antigua* and also my manors, lands, tenements and hereditaments situate and being in the said County of Devon and elsewhere in England with their and every(?) of their rights, members and appurtenances unto the Reverend John Tripe, son of ____Tripe surgeon of Ashburton....'

Will of Esther Swete, 23 Feb 1781, National Archives PROB 11/1075/73

*For more on the connection of the Swete family to slavery in Antigua, see The Swete family in Modbury

http://www.blacknetworkinggroup.co.uk - Accessed 6-4-2014

'Trewin, now called Trayne or Traine*...about the middle of the sixteenth century the heiress of Scoos brought it to the Swetes. Adrain Swete Esq., the last of this family, died in 1755, having bequeathed all his estates to his mother, Mrs Esther Swete, who died in 1771 having devised them to her relation the Rev John Tripe of Ashburton (now of Oxton), who took the name of Swete and is the present proprietor.

*Modbury

Magna Britannia, Daniel and Samuel Lysons, London 1822, vol 6, part 2 p345

Image courtesy ancestryimages.com

In 1871 a Mr Pengelly, reading to the Devonshire Association, quoted extracts from the manuscript volumes of 'Picturesque Sketches of Devon' by the Rev John Swete, described as being in twenty thick volumes. Mr Pengelly had been lent the volumes by a Mrs. Sweete of Torquay.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 25 August 1871 p6 col7

These illustrated journals for 1789 to 1800, edited by Todd Gray and Margery Rowe, have been published by the Devon Records Office and Devon Garden Trust in four volumes entitled 'Travels in Georgian Devon.'

He died in 1821:'Lately, the Rev John Swete, Prebendary of the Cathedral Church of Exeter.'

His will, catalogued under the Rev John Swete, Clerk of Oxton House, can be found in the National Archives

Bury and Norwich Post 7 November 1821 p2 col4

National Archives PROB 11/1651/278

*******

Dr John Ireland

According to the website of Westminster Abbey John Ireland was born on 8 September 1761 at Ashburton, the son of butcher Thomas and his wife Elizabeth.

http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/people/john-Ireland Accessed 5-11-2013

There

is certainly a Thomas Ireland who was a butcher in Ashburton in the

1780s and 90s. He takes on Thomas Endle as an apprentice in 1783,

Richard Smerdon as an apprentice in 1784 and William Ireland in 1791.

Register of duties paid for Apprentices' Indentures 1710-1811

In a report

made just after his death, the Western Times stated that he had one

brother, the late Thomas Ireland, and one sister, the late Mrs Searle.

Western Times 10 September 1842 p3 col4

In view of the above, it seems likely that John was in fact the son of Thomas and Sarah, baptised on 29th September 1761. They already had children Thomas and Sarah.

Sarah (Jnr) later married Thomas Searle.

https://familysearch.org/search

A Thomas Ireland, butcher, features in A transcript of trades and professions from the Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce and Manufacture, Vol 2, late 1700s.

See Occupations in the 1600s and 1700s, in the sub-menu to the Banks and businesses section.

Presumably the same Thomas Ireland also appears in the Devon Freeholders Book of 1771

http://www.foda.org.uk/freeholders/

QS7/44/teignbridge.htm Accessed 6-11-2013

According to a newspaper report in 1891, The Devon and Cornwall Bank (most recently, the NatWest Bank) was built on the site of where Dean Ireland had once lived.

Western Morning News 20 April 1891, p3 col3

Educated at the Grammar School, John became a curate near Ashburton after attending college, and later became a vicar at Croydon.

Western Times 10 September 1842 p3 col4

Again according to the Westminster Abbey website he became sub-dean of Westminster in 1806 and Dean in 1816.

http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/people/john-Ireland Accessed 5-11-2013

A letter from Robert Barks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool, from Coombe Wood, 22 December 1815, announced various appointments that the Regent had agreed. They included (ff.66v.) the appointment of (John) Ireland as Dean of Westminster and (James) Webber, late chaplain to the Speaker to Ireland's canonry. The letter also discusses the living of Croydon which Ireland was to vacate (f.66).

The Manners Sutton Papers, ref MS 3274 1687-1827 in Lambeth Palace Library

In 1837 the Dean and Chapter of Westminster were amongst those against the opening of various public buildings, including Westminster Abbey, to the public. They were not convinced that visitors would appreciate the difference between a place of worship and 'a common exhibition room'. They pointed out that on a previous occasion when part of the Abbey was open, there was 'indecorous behaviour and constant noise.'

Morning Post 18 December 1837 p2 col2

A statue of Lord Byron*, destined for Westminster Abbey lay in a packing case in the Custom House for four years after Dr Ireland prevented it being displayed in Westminster Abbey. He had already refused to have him buried there.

Kendal Mercury 25 August 1838 p4 col5

*'Mad, bad and dangerous to know' - Lady Caroline Lamb

1839. The vicar of Ashburton, the Rev Wm Marsh, was able to tell a meeting of the town that Dr John Ireland, Dean of Westminster, was intending to give £2000 to purchase suitable premises to house the master of the Grammar School.

He had already given £1000 to the town, the interest of which was given to six aged persons annually.

Westmorland Gazette 19 January 1839 p1 col4, quoting the Exeter Post

John Ireland died in 1842. His remains were interred in Westminster Abbey, in the same grave as William Gifford. The procession of singing men, choristers, alms-men, vergers and other officials stretched the entire length of the aisle parallel to Henry VII's chapel. The plain coffin had the inscription: 'The Very Rev John Ireland D. D. Dean of Westminster, died 2nd September 1842, aged 81 years.*'

Westmorland Gazette 17 September 1842 p4 col5

*The Western Times states that he was 'nearly 81'

The bells at St Andrews rang several mourning peals.

Western Times 10 September 1842 p3 col4

Above : Ireland House, East Street.

My own photograph 2012

Dr Ireland had given a scholarship at Oxford for the 'encouragement (of) classical learning' and the new Bishop of Manchester had been a recipient. The French Journal Official mistook the nature of the scholarship, thinking that a clergyman had been promoted who had a knowledge of the Irish language and with Irish sympathies

Berkshire Chronicle 5 February 1870 p2 col5

Left: John Ireland, Dean of Westminster

From Wikimedia Commons, in the public domain

'The Dean of Westminster, carrying the crown....'

Account of the coronation of George IV, Yorkshire Gazette 28 July 1821 p4 col4

*******

John Dunning, 1st Lord Ashburton

'His stature was of the smallest, and his limbs, though none of them absolutely deformed, (unless, indeed, considerable bandiness, and an unusual protusion of the shin bones in front, may be said to have merited that title for his legs) were ill-shaped and awkwardly put together; nor were the defects of his figure at all atoned for by any counterbalancing beauties of countenance.'

Available through Wikimedia Commons - Accessed 14-12-2013

'Lord Thurlow is said to have caused a note to be delivered to him at Dunning's club by telling a waiter "to deliver it to the ugliest man at the card table—to him who most resembles the knave of spades." '

G.E. Cokayne; with Vicary Gibbs, H.A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, editors, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed., 13 volumes in 14 (1910-1959; reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, U.K.: Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000), volume I, pp 275,276. Available through http://www.thepeerage.com - Accessed 14-12-2013

'His family was, originally from Guatham*, in the neighbourhood of Tavistock........but his father** had settled at Ashburton....where he practised as an attorney. He had married the daughter of a Mr Henry Judsham, of Old Port, in the parish of Modbury***.....The John Dunning of whom we have hear to speak was his second son.

He was born on the 18th October 1731 in the house where his father resided and carried on his business, which house is still standing, and is pointed out at this day to the stranger by the townspeople of Ashburton, with no little pride and complacency.'

Lives of eminent English judges of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, William Newland Welsby, T & J W Johnson, Philadelphia 1846, p535

*Gnatham ? See the Walkhampton section on Genuki http://www.genuki.org.uk/ - Accessed 21-12-2013

Charles Worthy, in 'Devon Parishes', says it is Gnatham. Charles Worthy, Devonshire Parishes, Exeter and London 1887, vol 1, p73

A document in the Devon Record Office - 48/14/65/7a-b 3, 4 July 1753, concerning a former slaughter house in St Lawrence Lane names John Dunning of Ashburton, gent, and Richard Dunning of Walkampton, gent, his brother.

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/a2a - Accessed 23-12-2013

** Charles Worthy says born 1701, Charles Worthy, Devonshire Parishes, op cit. p 73

*** Henry Jutsham according to Charles Worthy, Devonshire Parishes, op cit. p 73. Marriage licence said to be 17th May 1726.

According to the Devon Rural Archive website, Lord Ashburton acquired Oldaport, Modbury, sometime before 1801

http://www.devonruralarchive.com/Oldaport.html - Accessed 23-12-2013

According to The Complete Peerage he was the son of John Dunning and Agnes Judsham, probably the same John Dunning as was baptised on 29 October 1731 at Ashburton, son of John.

1737 John Dunning, attorney in Ashburton, has an apprentice, Arthur Hele of Diptford. He has George Woodward Mallet as an apprentice in 1753, Thomas Gifford in 1755, John Edmonds in 1762 and Deeble Peter in 1769.

Register of duties paid for Apprentices' Indentures 1710-1811

Charles Worthy states that he was believed to have been born at the Perrys' house in Gulwell, which was actually in Staverton parish. 'Still in existence' in 1887, it was behind the modern (at that date) house of the Perry family. Built partly of cob, it had oak interior woodwork, some of which was carved. There were also six figures, apparently painted on leather and fixed to one of the panels. The house featured a Tudor window and late perpendicular doorways, but by the time of the article was being used as a store room.

The same writer says that by 1736 John Dunning senior was the owner of a house in West Street.

Charles Worthy, Devonshire Parishes, op cit, pp 73,74

Right: The date, 1775, incised in the stone.

My own photograph, 2014

In 1864 land in the Ashburton area, including Gulwell Meadow or Mead was put up for sale. Although technically in Staverton, the advertisement said it was number 2084 on the tithe map.

Exeter and Plymouth Gazette 15 July 1864 p1 col4

He attended the Grammar School at about the age of seven, and according to 'Lives of eminent judges' had as a master the Rev Hugh Smerdon, 'curate of the neighbouring parish of Woodlande' and the same master who taught William Gifford twenty five years later (op cit p 236). However W S Graf says that the master of the Grammar School, from c 1730 to c 1770 was the Rev Thomas Smerdon

Ashburton Grammar School, 1314 - 1938, W S Graf, printed S T Elson, Ashburton, p63.

'Dunning has often been heard to declare later in life that he owed all his success to Euclid and Newton. Whatever intimacy he had cultivated with the last of these was not commenced, we are inclined to think, at Ashburton school.'

Lives of eminent judges, op cit p 536

Leaving school at about age 13, Dunning became an articled clerk in his father's firm.

'Several monuments of his industry as a clerk are still to be met with in the neighbourhood of Ashburton, such, for instance, as family deeds and settlements, written throughout by his own hand, and bearing his signature as an attesting witness. Many pages also of the proceedings in the parish books are of his writing, and are signed J Dunning, junior.'

Dunning's talents were allegedly discovered when, at about the age of nineteen, he prepared a document in his father's absence, and sent it to Sir Thomas Clark, Master of the Rolls. When his father returned and learned what he had done, he immediately sent an apology to Sir Thomas for any errors. However, Sir Thomas was so impressed with the document that he recommended that John should be sent to the bar, and as a result was entered into Middle Temple on May 8th 1752.

ibid pp 536 -538

He became friendly with a man called Kenyon, and a man called Home (later Home Tooke) and they often dined at a small eating house near Chancery Lane.

'Dunning and myself* were generous...for we gave the girl who waited upon us a penny a-piece; but Kenyon, who always knew the value of money, sometimes rewarded her with a halfpenny, and sometimes with a promise.'

*ie Tooke

ibid p 539

Although records stated that he was called to the bar in 1756, the authors of 'Lives of eminent judges' doubt that this is correct, as there would then be less than five years between admission to Middle Temple and his call to the bar.

ibid notes pp 539, 540

Dunning began to make a reputation for himself during a dispute between the Dutch and the English East India Companies. He was commissioned to reply to a complaint made by the Dutch, which he did in what became a forty five page pamphlet, entitled ' A defence of the United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies, and their servants (particularly those at Bengal), against the complaints of the Dutch East India Company; being a memorial from the English East India Company to his Majesty on that subject

His work steadily increased. But at the end of 1763 he became involved in a case that 'at one single bound ' raised him to eminence.

The Secretary of State had issued a warrant for the arrest of people involved in the publication of the North Briton. One of these was a bookseller named Leach, who was now suing after being imprisoned and having his papers seized. Through Dunning's efforts Leach won £400 damages.

ibid pp 540-545

http://www.oxforddnb.com- Accessed 18-12-2013

Having been chosen Recorder of Bristol, by 1767 Dunning had become Solicitor-General.

In 1768 he entered Parliament, becoming member for Calne; he was re-elected in 1774 and 1780.

His legal work increased 'to average full ten thousand a year', although he would take on cases for nothing if he thought the cause a just one. He made 'not the slightest distinction (and some counsel are apt to make a great deal) between the most profitable and the least.'

Lives of eminent judges, op cit pp 544, 545

Dunning could now afford a liberal lifestyle, but this was not appreciated by his mother. 'The old lady was a thrifty housewife, and had trained up her boy John in the ways of strict frugality, a fact whereof some amusing illustrations are still traditionally preserved among the townspeople of Ashburton.......if her son expected to be complimented by her on his style of living, he was grievously disappointed......two tureens of soup, and two dishes of fish, for one dinner, she said, would in time be the ruin of him....'

ibid pp 561,562

On March 31st 1780, John Dunning married Elizabeth Baring, the daughter of John Baring of Exeter.*

*At St Leonard, Exeter

Above: A painting in the Town Hall of John Dunning and his wife Elizabeth (according to the Tate Gallery) However this painting has long been referred to as Lord Ashburton and his sister Mary Dunning. After the painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds 1782

Many thanks to John Germon for this photograph.

In December of the same year his father died.

Lives of eminent judges op cit pp 563,564

His father's will left 'the house wherein I now live' in Ashburton to his daughter Mary Dunning, together with the plate, furniture and household goods that the house contained, plus two thousand pounds. The rest of his real and personal estate he left to his son John, who was also his executor.

John Dunning Snr asked that he be buried as quietly as possible in the early morning, carried to his grave by eight labourers, who were to receive five shillings apiece 'for their trouble'.

A note at the end of the will states that in January 1784 the administration of the estate passed to John Baring and John Morris, two of the executors of the will of the Right Honorable John Lord Ashburton deceased, 'the said John Lord Ashburton surviving the said testator but dying without having taken upon him the execution thereof.'

National Archives catalogue ref Prob 11/1112

John Dunning Jnr was created 1st Baron Ashburton, of Ashburton, Devon on 8 April 1782

The Complete Peerage, op cit p 275

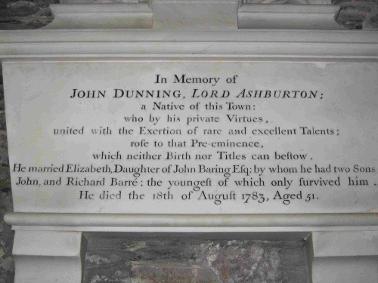

Above: Close up of the memorial to John Dunning, St. Andrew's Church, Ashburton.

My own photograph 2014

*******

The Various Lords Ashburton

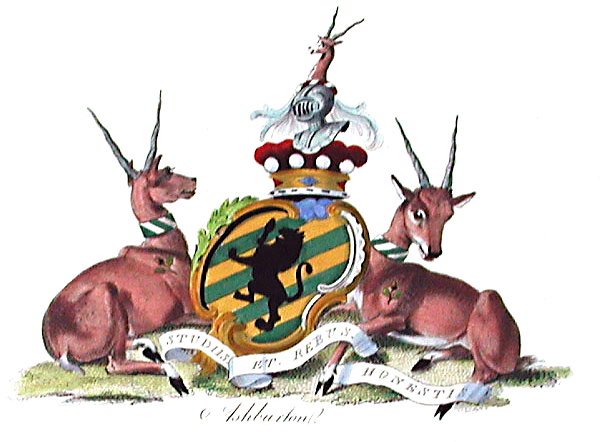

Above: Image from Catton's English Peerage,1790

available through Wikimedia Commons

From Kearsley's Complete Peerage 1799:

John. the late Lord Ashburton, was born Oct 18 1731....on April 9 1782 was created a Peer.

His Lordship married, March 31 1770, Elizabeth Baring, daughter of John Baring Esq of Larkbear near Exeter, born 1744, by whom he had issue, John, born Oct 29 1771, who died on April 4 1772; and Richard Barre, the present Lord, who succeeded on the death of his father, the late Lord, Aug 18 1783.

Richard-Barre Dunning, Lord Ashburton, Baron of Ashburton ,in Devonshire, born September 20th 1782

Heir apparent. His Lordship being a minor, if he dies without issue male, the title will be extinct.

Kearsley's Complete Peerage of England Scotland and Ireland, 46 Fleet Street, London 1799, p226

Richard Barre Dunning, 2nd Baron Ashburton, lived until 15 February 1823. He married Anne Selby Cunninghame in 1805, but died without issue. The title then became extinct.

http://www.thepeerage.com/p2497 - Accessed 31-12-2013

However, the title was recreated a second time. Alexander Baring, born 27 October 1774, was the son of Francis Baring, one of the founders of Baring's Bank.

http://www.baringarchive.org.uk - Accessed 31-12-2013

He became 1st Baron Ashburton, of Ashburton, Devon on 10 April 1835.

This is the Lord Ashburton who negotiated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842

http://www.thepeerage.com/p1197.- Accessed 31-12-2013

*******

The Ashburton Shield.

The 2nd Baron Ashburton, William Bingham Baring, presented, in 1861, the Ashburton Challenge Shield as a prize for competition shooting between public schools. These competitions were held by the National Rifle Association, originally at Wimbledon (from 1860) but from 1890 at Bisley.

http://www.thepeerage.com/p1348.htm - Accessed 2-1-2014

Kelly's Directory of Surrey 1938, available at

http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/

~engsurry/bisley/kellys38.htm - Accessed 2-1-2014